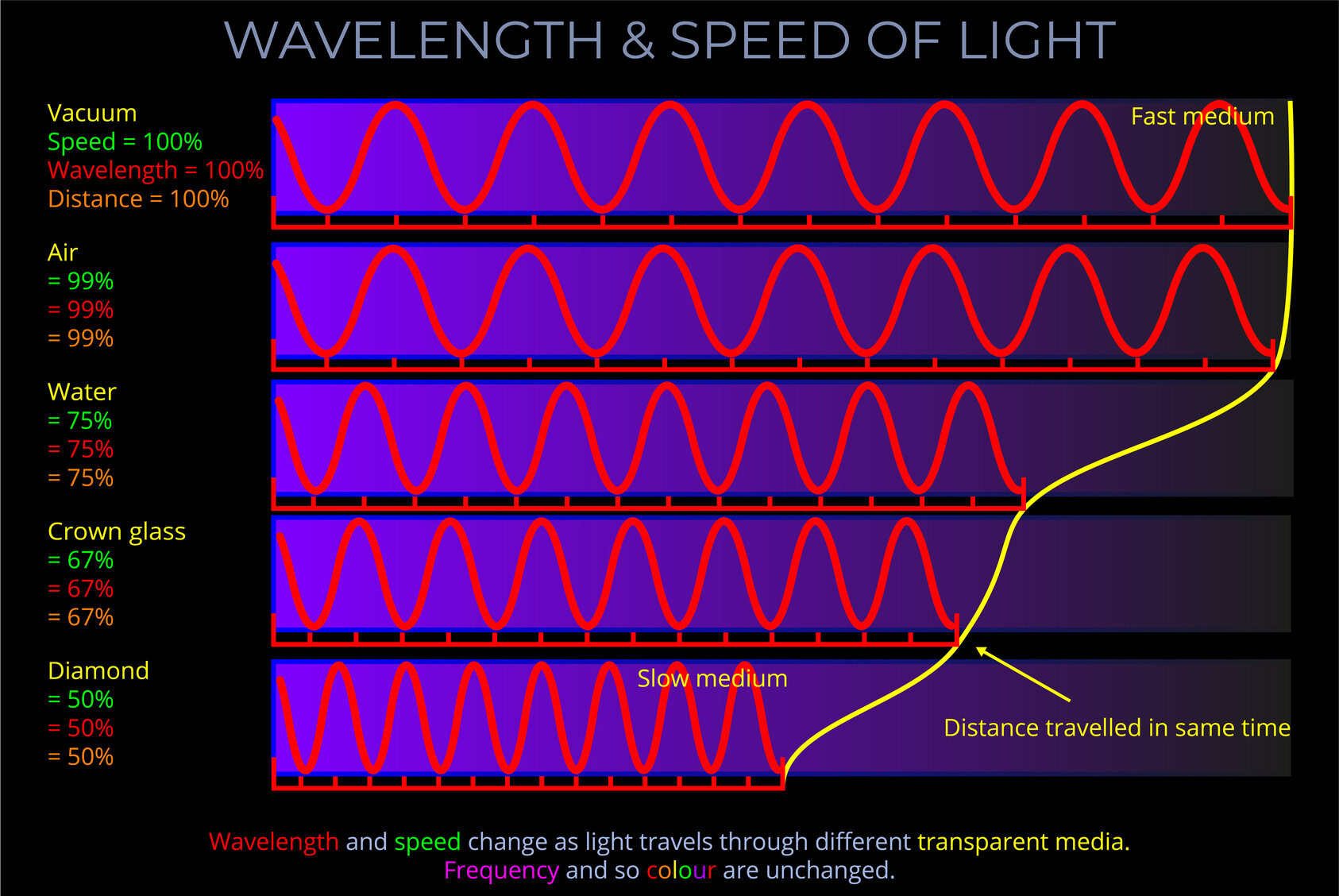

Light travels at different speeds through various media, such as air, glass, or water. A “fast” medium is one where light moves more quickly compared to other materials.

- In a vacuum, light travels at 299,792 kilometres per second, but in other media, it slows down.

- In some cases, the speed is close to that in a vacuum, while in others, it is significantly slower.

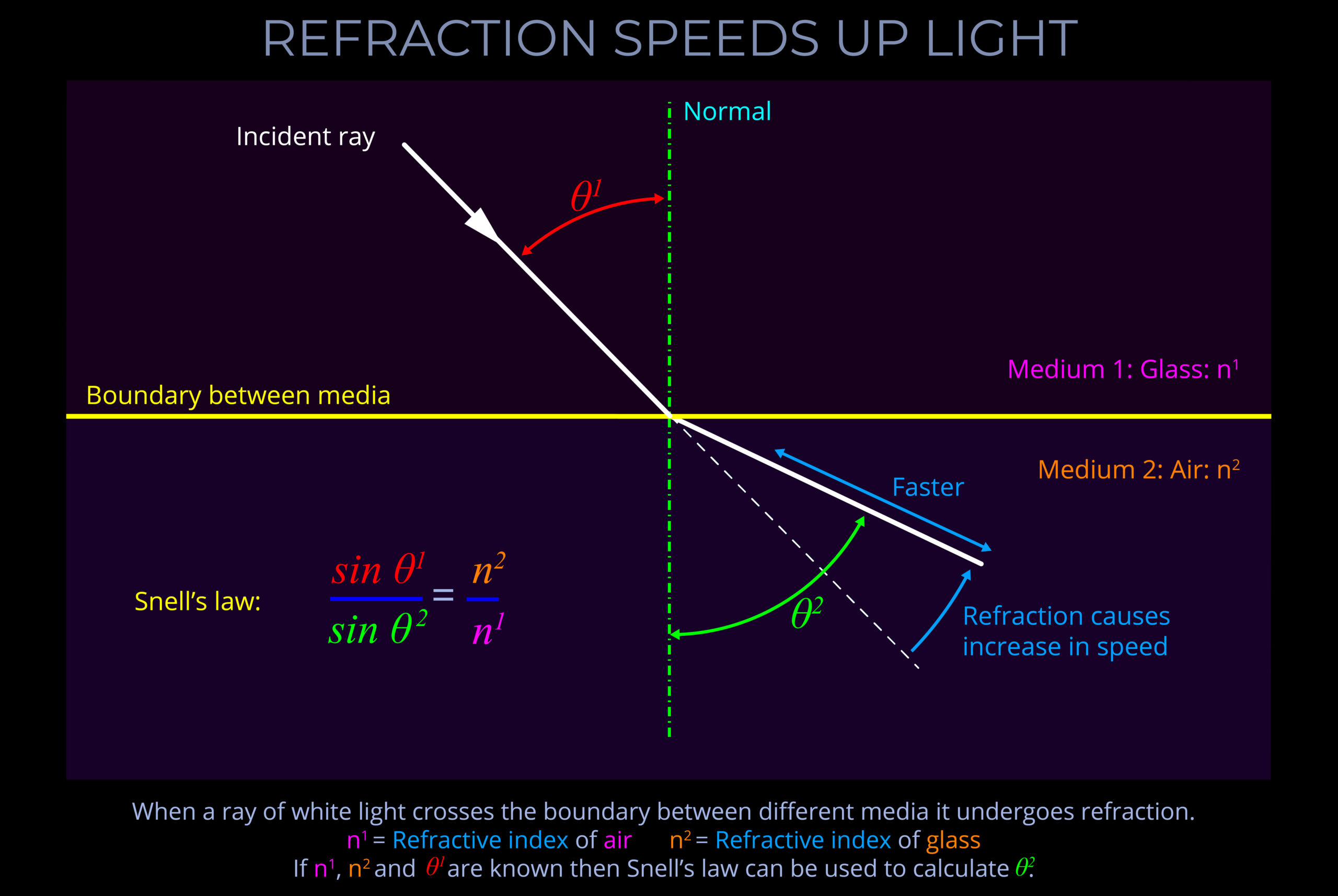

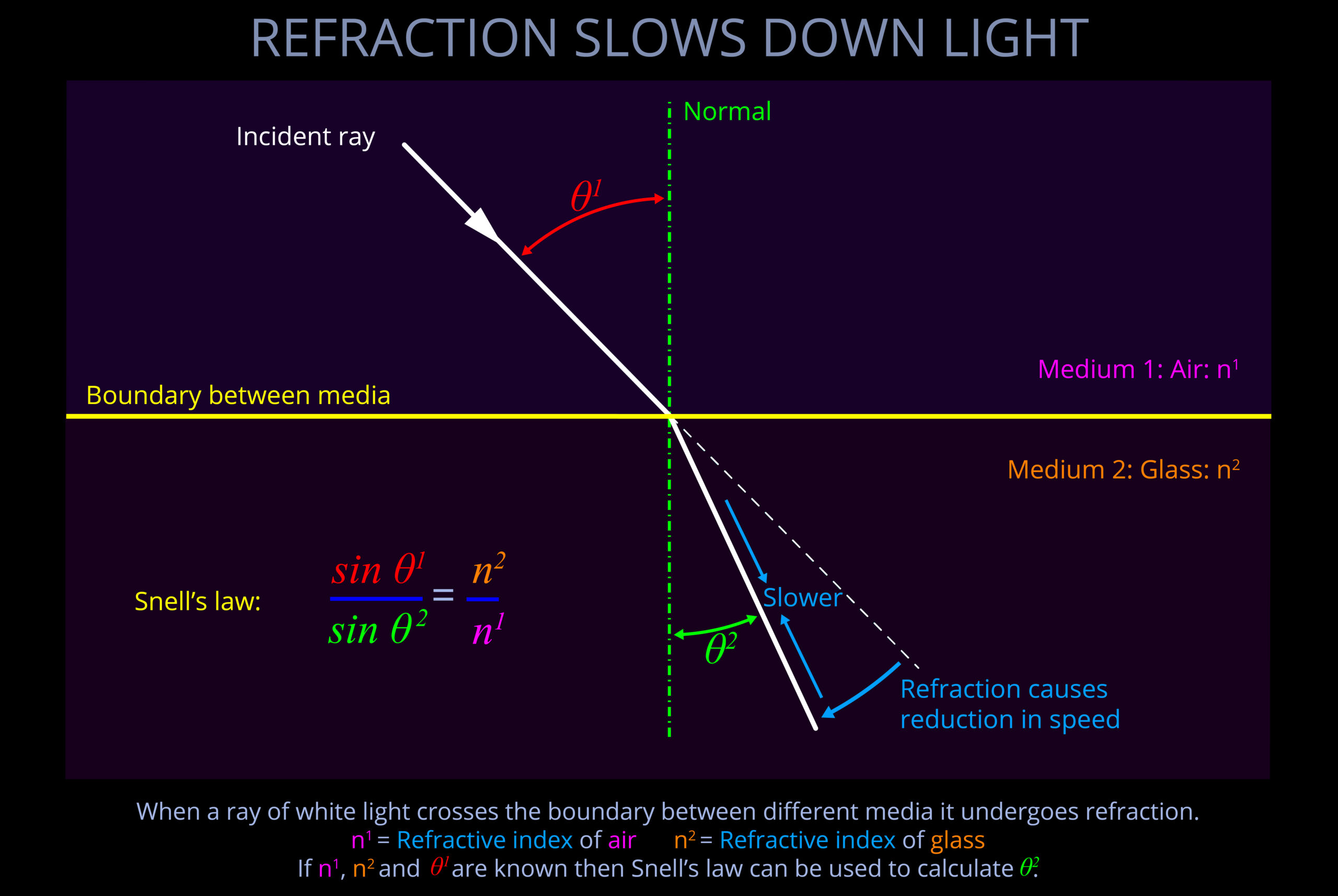

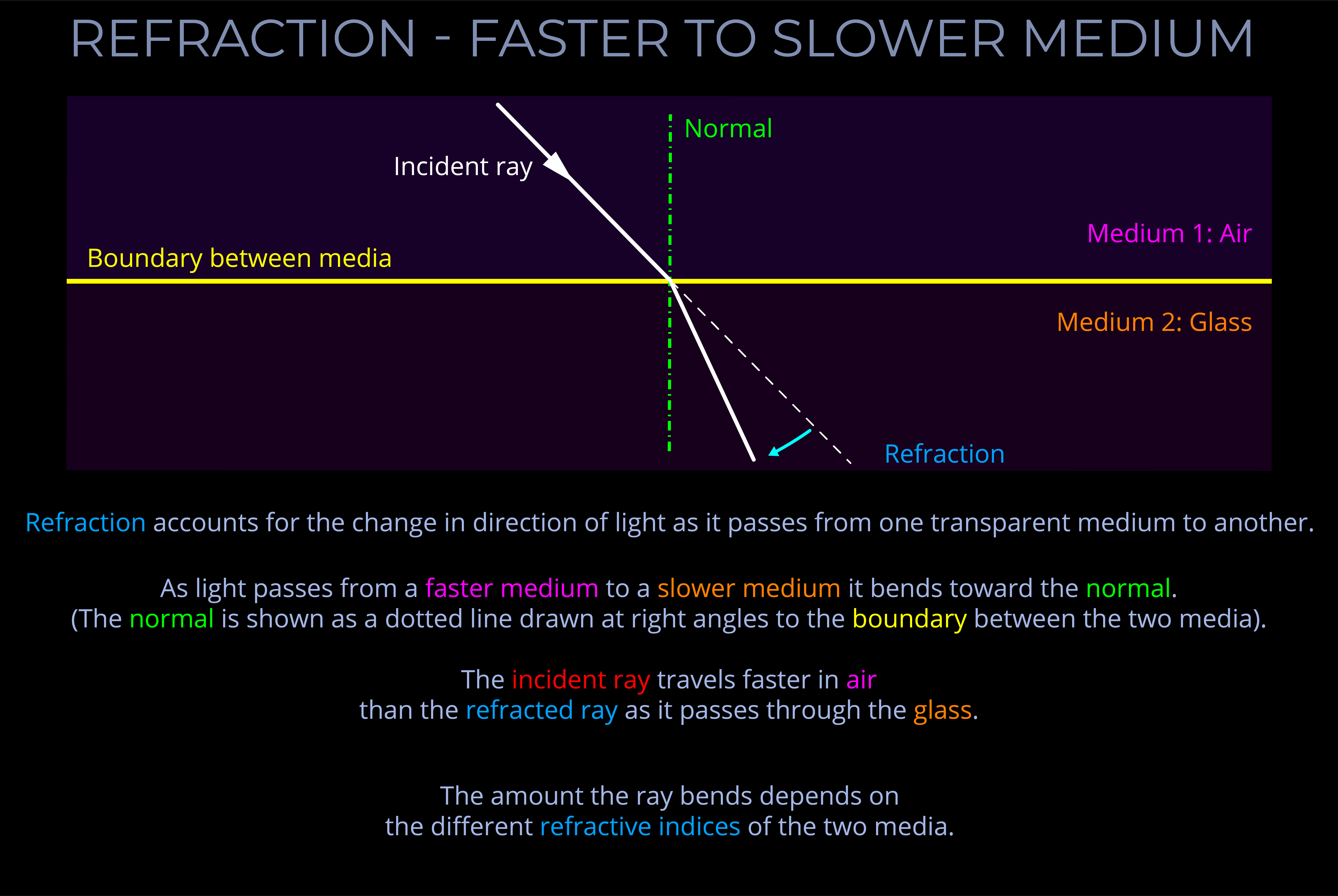

- Knowing whether a medium is fast or slow helps predict how light will behave when it crosses from one medium to another.

- If light crosses from a fast medium to a slower one, it bends towards the normal.

- If light crosses from a slow medium to a faster one, it bends away from the normal.

- In optics, the normal is a line drawn perpendicular (at a 90° angle) to the boundary between two media in a ray diagram.

An electromagnetic field (which includes both electric and magnetic fields) is the region around an object where it can exert a force on another object without direct contact. Electric fields arise from charged objects, while magnetic fields are produced by moving charges, such as electric currents.

- Fields are fundamental in physics, playing key roles in areas like electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, and general relativity.

- Fields can be represented by lines showing the direction of the force experienced by objects within the field.

- Fields are created by a source object and influence other objects within their range.

- Electromagnetic fields combine electric and magnetic components, interconnected through electromagnetic waves.

- Electric fields are associated with positive or negative charges and exert forces on charged objects.

- Magnetic fields are generated by moving electric charges, such as currents in wires, and can affect magnetic materials and charged particles.

- Electric fields and magnetic fields together make up the electromagnetic field, which governs interactions between charged particles.

- According to quantum field theory, all particles and forces in the universe arise from interactions between underlying fields, which give rise to the properties of matter and energy.

Fluorescence is a type of luminescence, a light source resulting from the temporary absorption and emission of electromagnetic radiation by certain materials.

- Fluorescence occurs when these materials “catch” light of a specific colour and then quickly “re-emit” it as a different, usually lower-energy (longer wavelength) colour.

- Unlike light sources that involve flames or extreme heat, fluorescence happens through a rapid physical process in the material itself.

There are many optical effects similar to rainbows.

- A fog bow is a similar phenomenon to a rainbow. As its name suggests, it is associated with fog rather than rain. Because of the very small size of water droplets that cause fog, a fog bow has only very weak colours.

- A dew bow can form where dewdrops reflect and disperse sunlight. Dew bows can sometimes be seen on fields in the early morning when the temperature drops below the dew point during the night, moisture in the air condenses, falls to the ground, and covers cobwebs.

- A moon bow is produced by moonlight rather than sunlight but appears for the same reasons. Moon bows are often too faint to excite the colour receptors (cone cells) of a human eye but can appear in photographs taken at night with a long exposure.

- A twinned rainbow is produced when two rain showers with different sized raindrops overlap one another. Each rainbow has red on the outside and violet on the inside. The two bows often intersect at one end.

- A reflection rainbow is produced when strong sunlight reflects off a large lake or the ocean before striking a curtain of rain. The conditions must be ideal if the reflecting water is to act as a mirror. A reflected rainbow appears to be similar to a primary bow but has a higher arc. Don’t get confused between a reflection rainbow that appears in the sky and a rainbow reflected in water.

- A glory is a circle of bright white light that appears around the anti-solar point.

- A halo is a circle of bright multicoloured light caused by ice crystals that appears around the Sun or the Moon.

- A monochrome rainbow only occurs when the Sun is on the horizon. When an observer sees a sunrise or sunset, light is travelling horizontally through the atmosphere for several hundred kilometres. In the process, atmospheric conditions cause all but the longest wavelengths to scatter so the Sun appears to be a diffuse orange/red oval. Because all other wavelengths are absent from a monochrome rainbow, the whole scene may appear to be tinged with a fire-like glow.

In physics, a force is anything that can make an object move differently. It’s like a push or a pull that can make an object start moving, stop moving, or change direction. Imagine kicking a soccer ball – the kick is the force that makes the ball move.

- Forces can be either contact forces or non-contact forces.

- Contact forces: These happen when two objects touch, like friction when you rub your hands together, or the push you give the ball.

- Non-contact forces: These act even when objects aren’t touching, like gravity pulling you down, or a magnet attracting a paperclip.

- Non-contact forces are forces that act between objects that are not in contact with each other. Examples of non-contact forces include gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong nuclear force.

- Forces can make things move faster (accelerate), slower (decelerate), or change direction altogether.

- Objects, bodies, matter, particles, radiation, and space-time are all in motion.

- On a cosmological-scale, concentrated matter in planets, stars, and galaxies leads to significant push-pull interactions.

- Motion signifies a change in the position of the elements of a physical system including translational motion, rotational motion, vibrational motion, and oscillatory motion.

Each fundamental force is conveyed by a distinct particle type known as a force carrier. These carriers are responsible for transmitting forces between pairs of particles.

- Take light as an example of a force carrier for electromagnetic radiation.

- Light is a form of energy that travels as waves, but it also behaves like a stream of tiny particles called photons.

- These photons are the force carriers for the electromagnetic force, one of the fundamental forces in the universe.

- The electromagnetic force is responsible for a variety of phenomena, including the attraction between oppositely charged particles and the repulsion between like charges.

- Photons can also interact with individual electrons in atoms, causing them to move or change energy levels.

- Follow this link to find out more about fundamental forces.

Fovea centralis

The entire surface of the retina contains nerve cells, but there is a small portion with a diameter of approximately 0.25 mm at the centre of the macula called the fovea centralis where the concentration of cones is greatest. This region is the optimal location for the formation of image detail. The eyes constantly rotate in their sockets to focus images of objects of interest as precisely as possible at this location.

The fovea centralis is the region of the eye that provides the optimal location for forming detailed images.

- The eyes continuously rotate in their sockets to focus objects of interest as precisely as possible onto the fovea centralis.

- These rapid movements, called saccades, position objects of interest on the fovea, allowing for detailed inspection of the environment.

- Although the entire surface of the retina contains nerve cells, the fovea is the small region (about 0.25 mm in diameter) at the centre of the macula which has the highest concentration of cones, making it ideal for capturing fine detail.

- While cones are concentrated in the fovea for detecting fine detail and colour, rods, which are more sensitive to light but not colour, are spread throughout the rest of the retina and are essential for peripheral and low-light vision.

A free electron is an electron that is no longer bound to a specific atom, allowing it to move freely within a material.

- Photoelectric Effect: Free electrons are involved in the photoelectric effect, where photons (light particles) strike a material and transfer energy to electrons. If the energy from the light is sufficient, it can release electrons from their bound state, creating free electrons. This phenomenon is fundamental to the operation of devices like solar cells and photodetectors.

- Interaction with Light: Free electrons can scatter light. When light interacts with a material, free electrons can absorb and re-emit photons, contributing to effects like reflection, refraction, and the generation of certain colours in materials.

- Plasma and Light: In a plasma state, which consists of free electrons and ions, light behaves differently compared to its behaviour in neutral gases. Free electrons can reflect and absorb electromagnetic radiation, influencing how light propagates through plasma.

- Electrical Conductivity and Light Emission: In conductors, free electrons facilitate electrical currents, and when these electrons transition between energy levels, they can emit light, as seen in incandescent bulbs or LED technology.

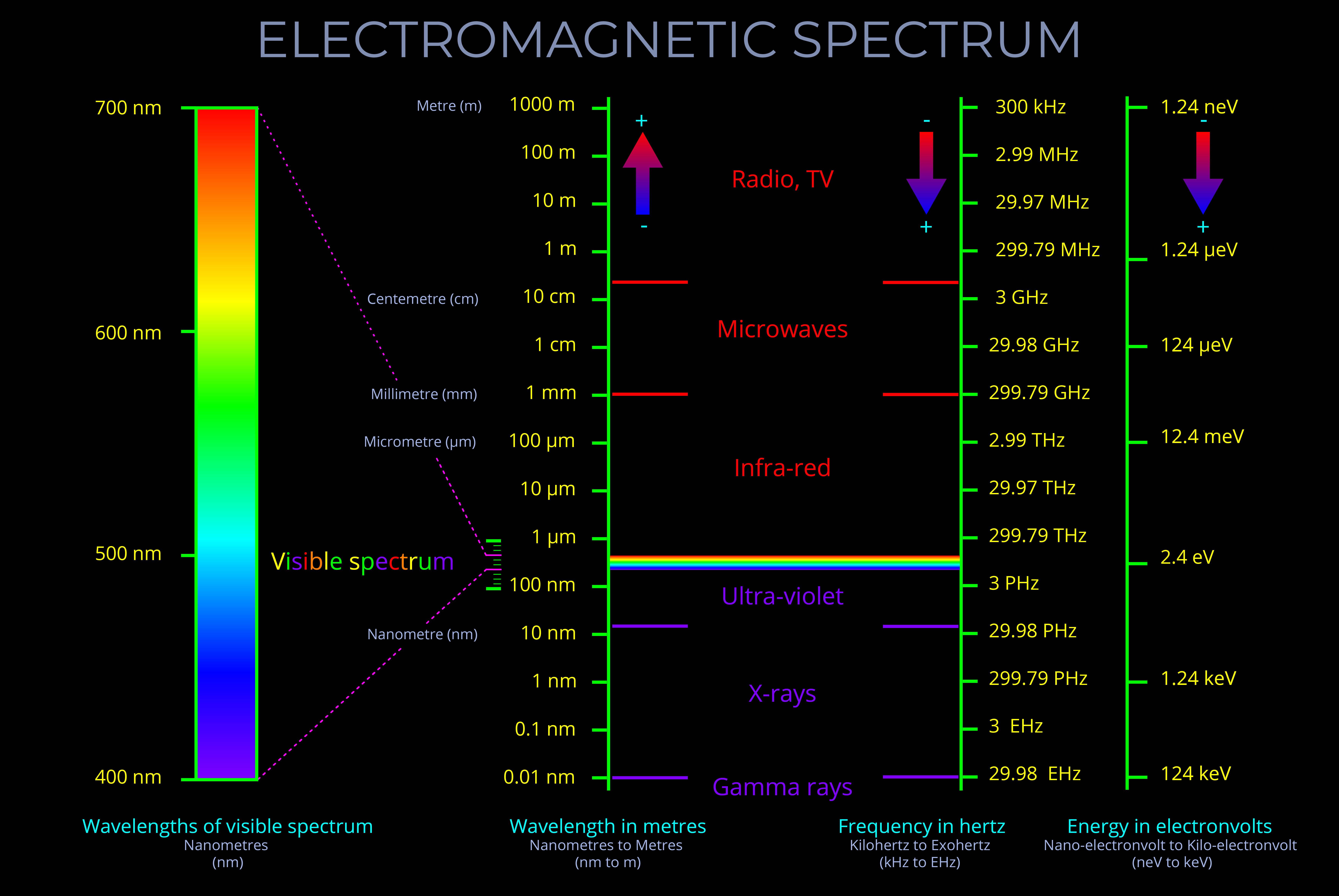

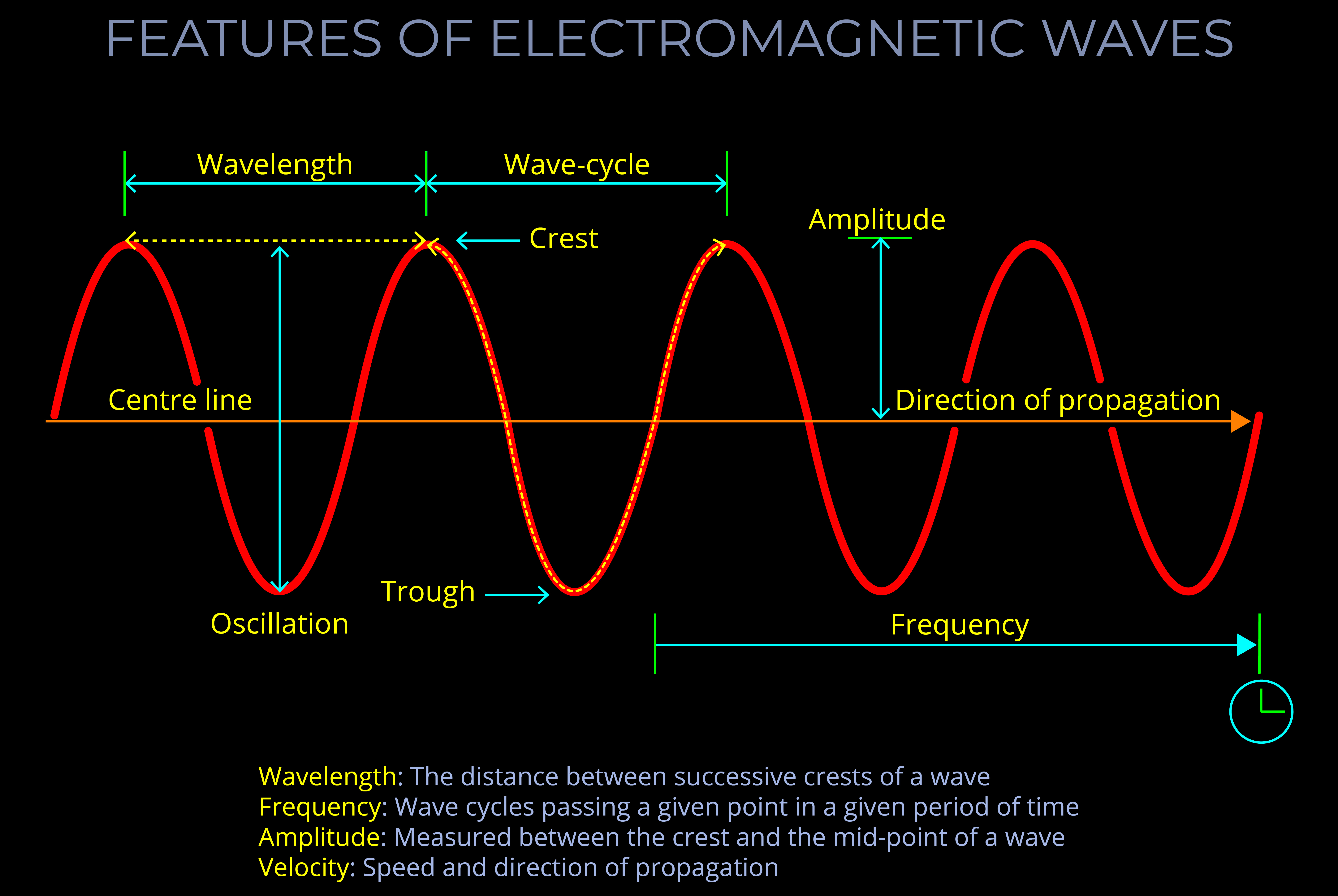

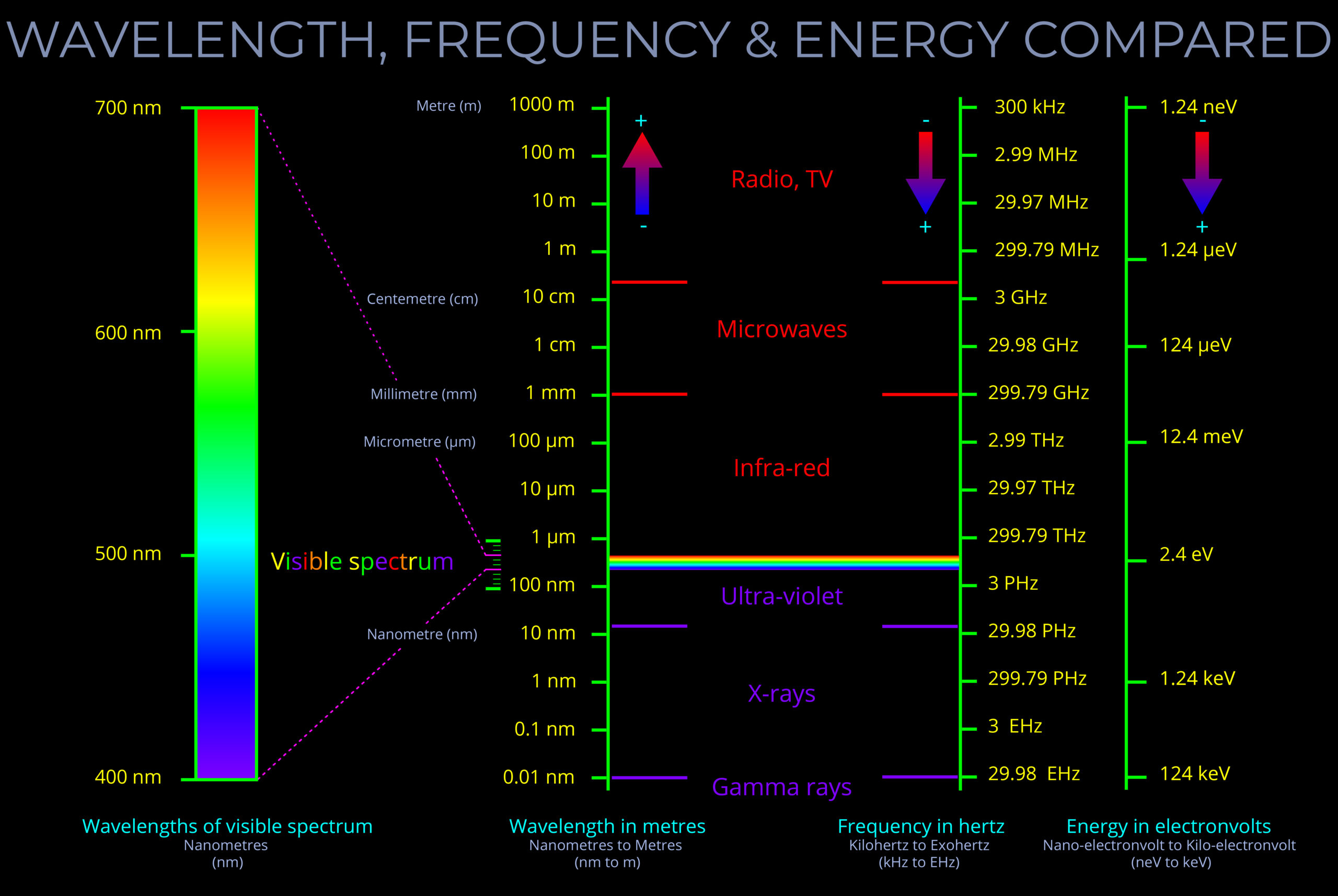

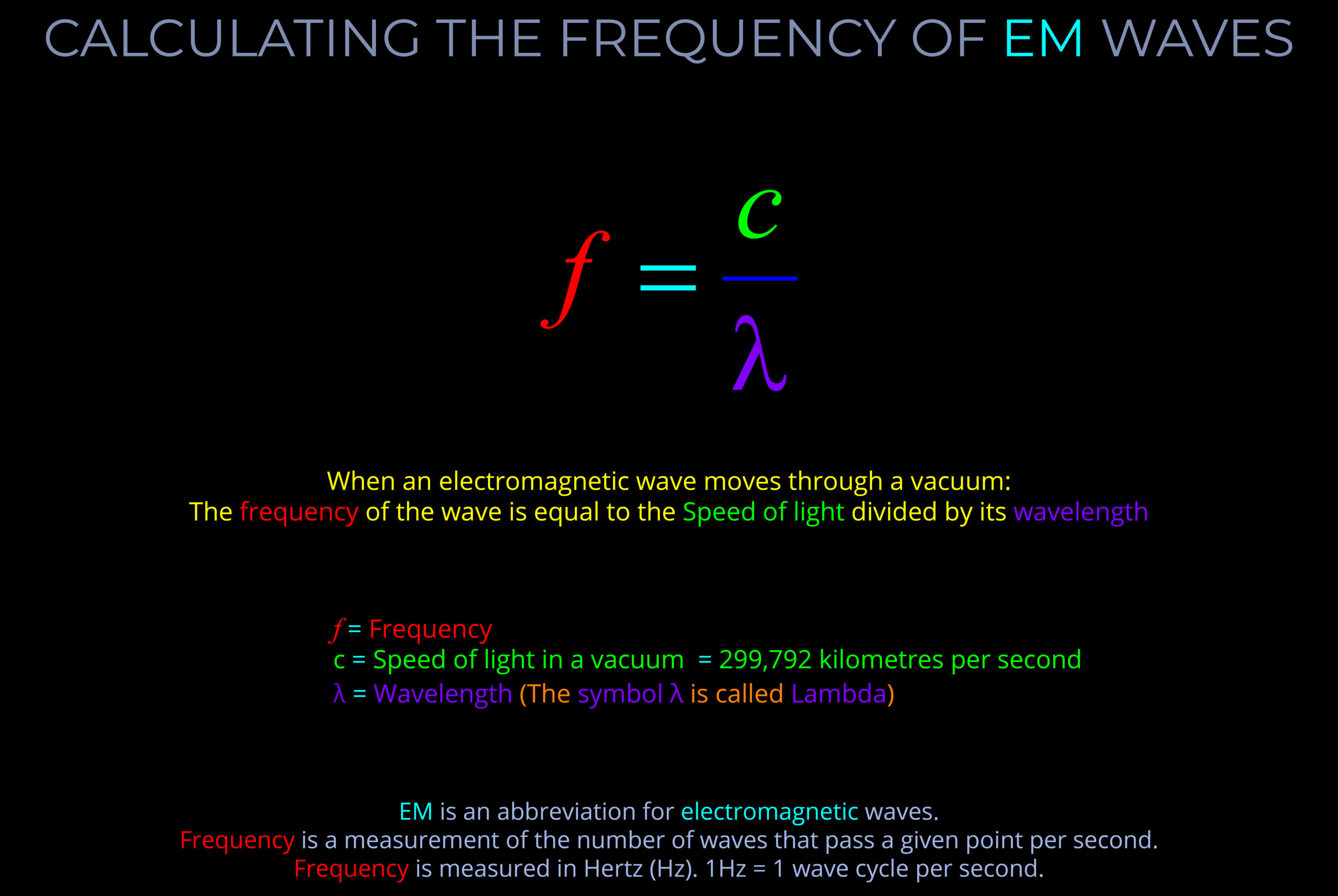

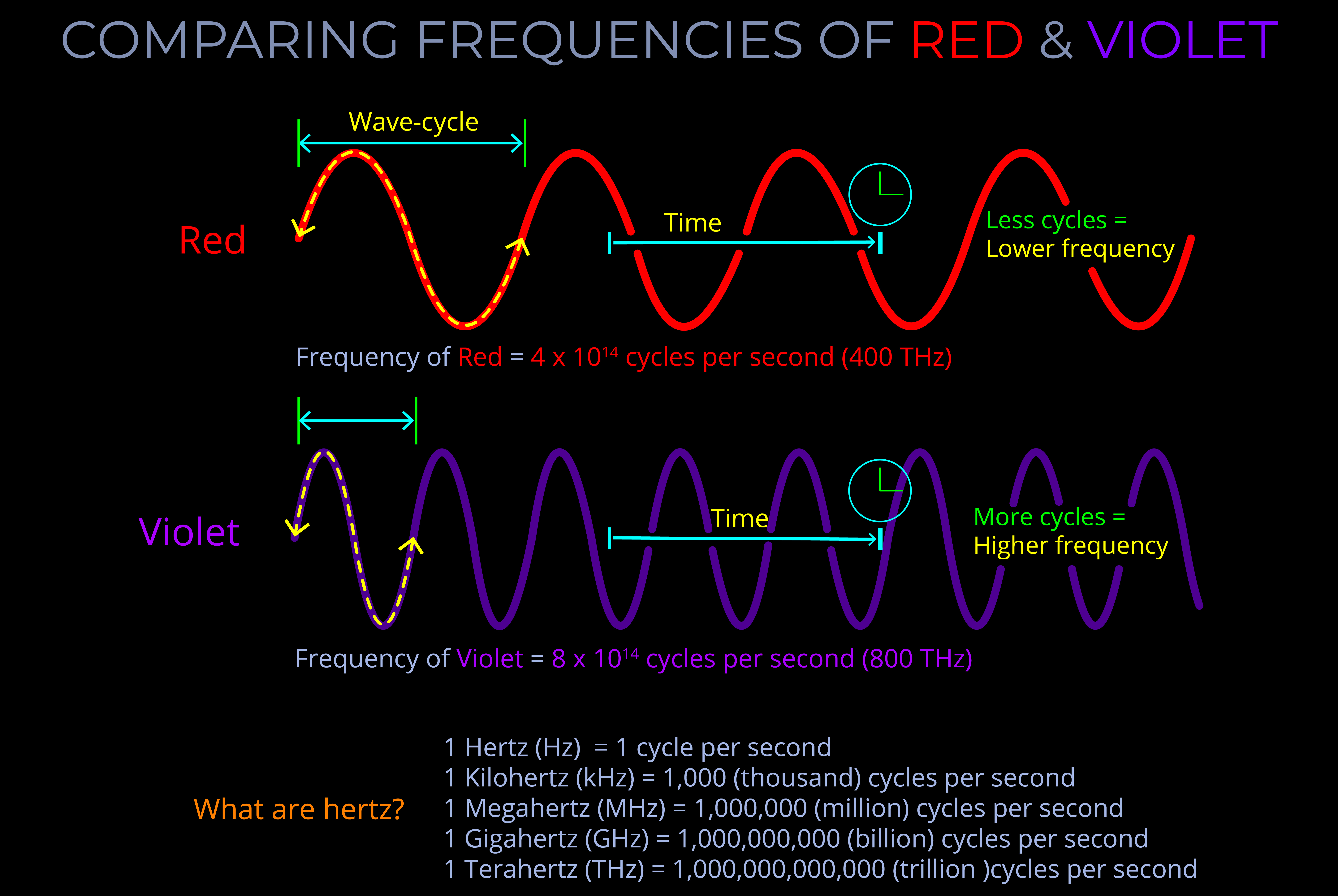

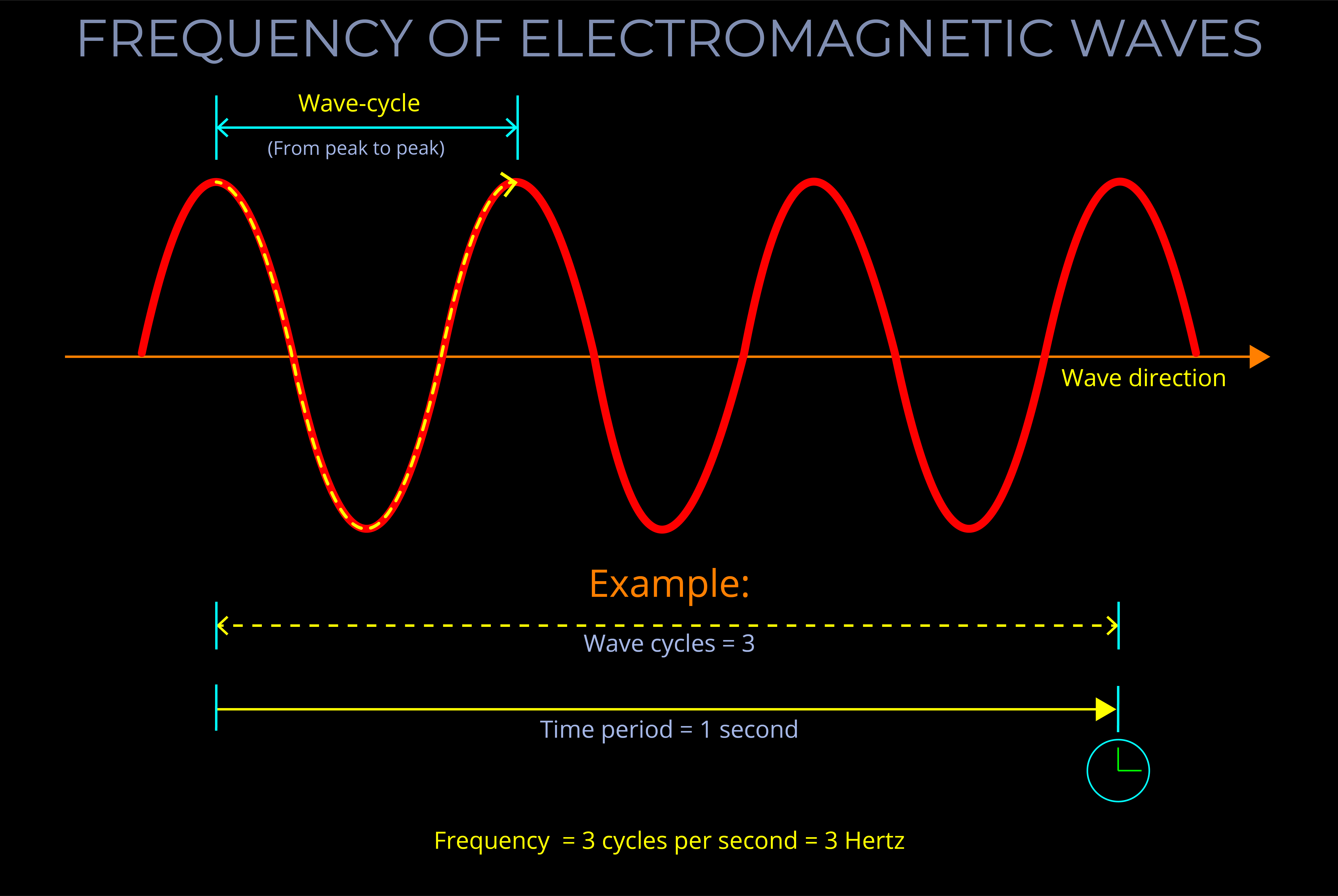

The frequency of electromagnetic radiation (light) refers to the number of wave-cycles of an electromagnetic wave that pass a given point in a given amount of time.

- Frequency is measured in Hertz (Hz) and signifies the number of wave-cycles per second. Sub-units of Hertz enable measurements involving a higher count of wave-cycles within a single second.

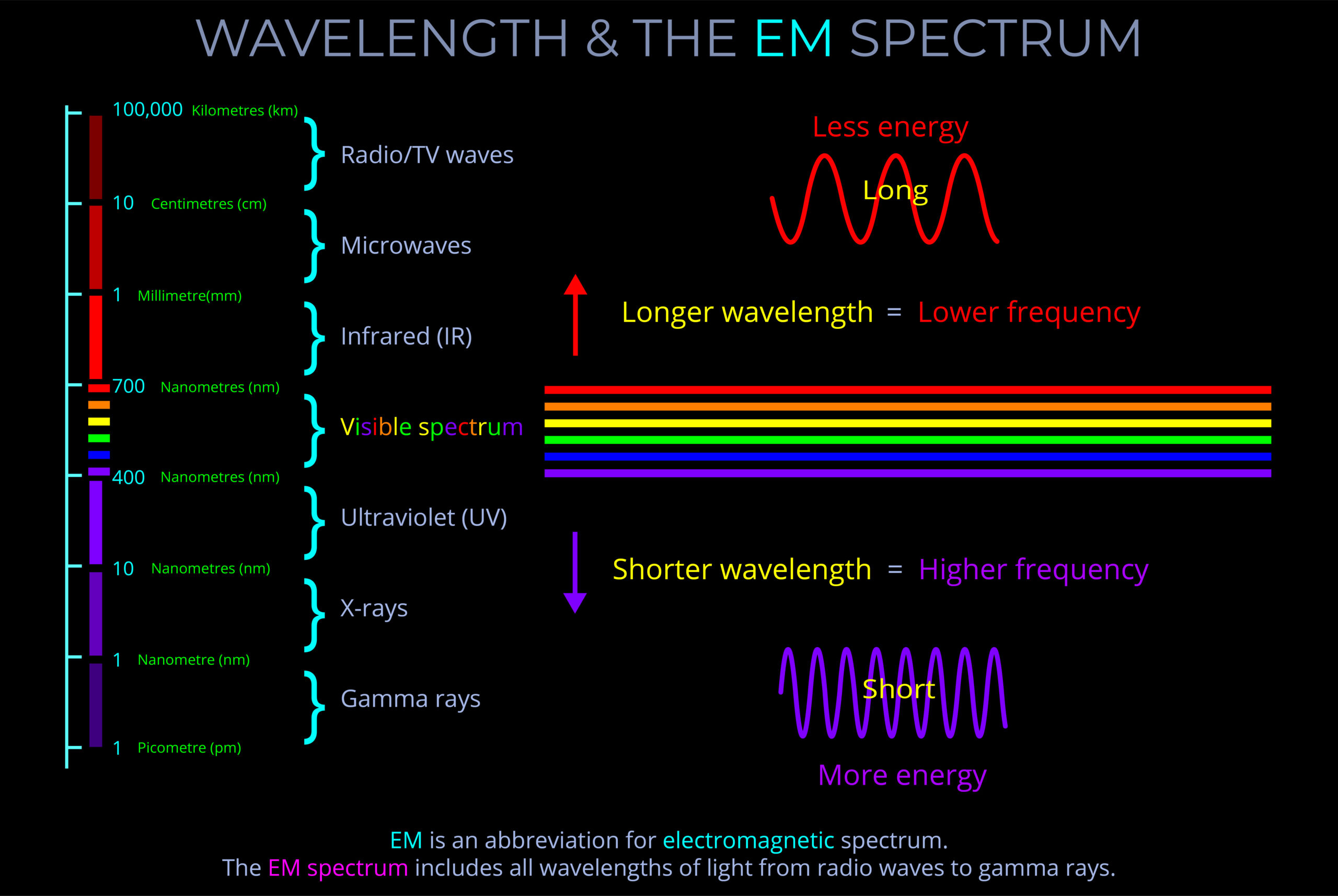

- The frequency of electromagnetic radiation spans a broad range, from radio waves with low frequencies to gamma rays with high frequencies.

- The wavelength and frequency of light are closely linked. Specifically, as the wavelength becomes shorter, the frequency increases correspondingly.

- It is important not to confuse the frequency of a wave with the speed at which the wave travels or the distance it covers.

- The energy carried by a light wave intensifies as its oscillations increase in number and its wavelength shortens.