Amacrine cells

Amacrine cells interact with bipolar cells and/or ganglion cells. They are a type of interneuron that monitor and augment the stream of data through bipolar cells and also control and refine the response of ganglion cells and their subtypes.

Amacrine cells are in a central but inaccessible region of the retinal circuitry. Most are without tale-like axons. Whilst they clearly have multiple connections to other neurons around them, their precise inputs and outputs are difficult to trace. They are driven by and send feedback to the bipolar cells but also synapse on ganglion cells, and with each other.

Amacrine cells are known to serve narrowly task-specific visual functions including:

- Efficient transmission of high-fidelity visual information with a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Maintaining the circadian rhythm, so keeping our lives tuned to the cycles of day and night and helping to govern our lives throughout the year.

- Measuring the difference between the response of specific photoreceptors compared with surrounding cells (centre-surround antagonism) which enables edge detection and contrast enhancement.

- Object motion detection which provides an ability to distinguish between the true motion of an object across the field of view and the motion of our eyes.

Centre-surround antagonism refers to the way retinal neurons organize their receptive fields. The centre component is primed to measure the sum-total of signals received from a small number of cones directly connected to a bipolar cell. The surround component is primed to measure the sum of signals received from a much larger number of cones around the centre point. The two signals are then compared to find the degree to which they agree or disagree.

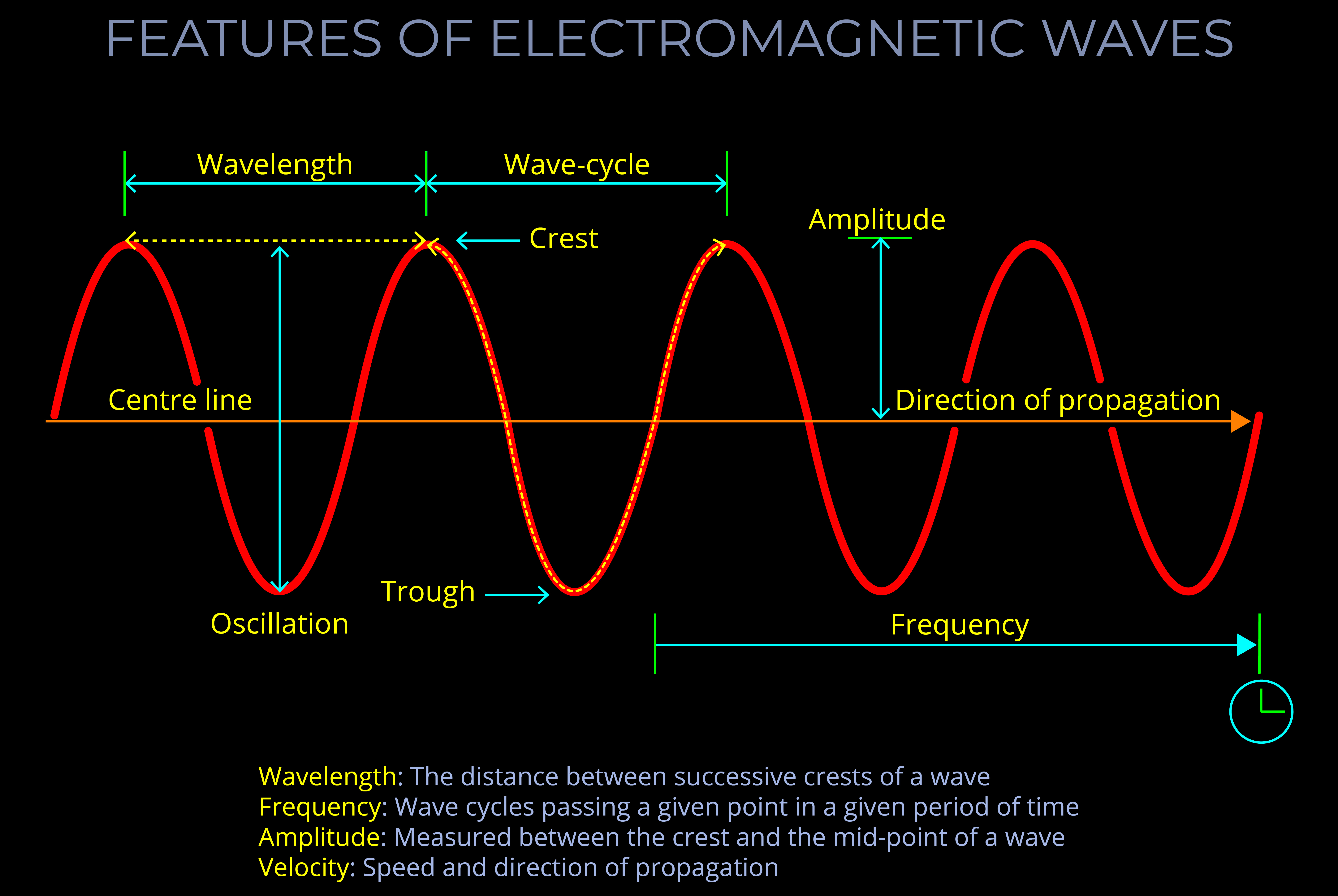

The amplitude of an electromagnetic wave is directly connected with the amount of energy it carries.

- In a wave diagram, the amplitude is represented as the distance from the centre line (or midpoint) of a wave to the top of a crest or the bottom of a corresponding trough.

- When the amplitude of an electromagnetic wave increases, the overall distance between any peak and the next trough also increases.

- The quantity of energy carried by an electromagnetic wave is proportional to the amplitude squared.

- Amplitude has an indirect correlation with the perception of the intensity of light and the brightness of colour as perceived by an observer because additional factors such as phase and interference must be taken into account.

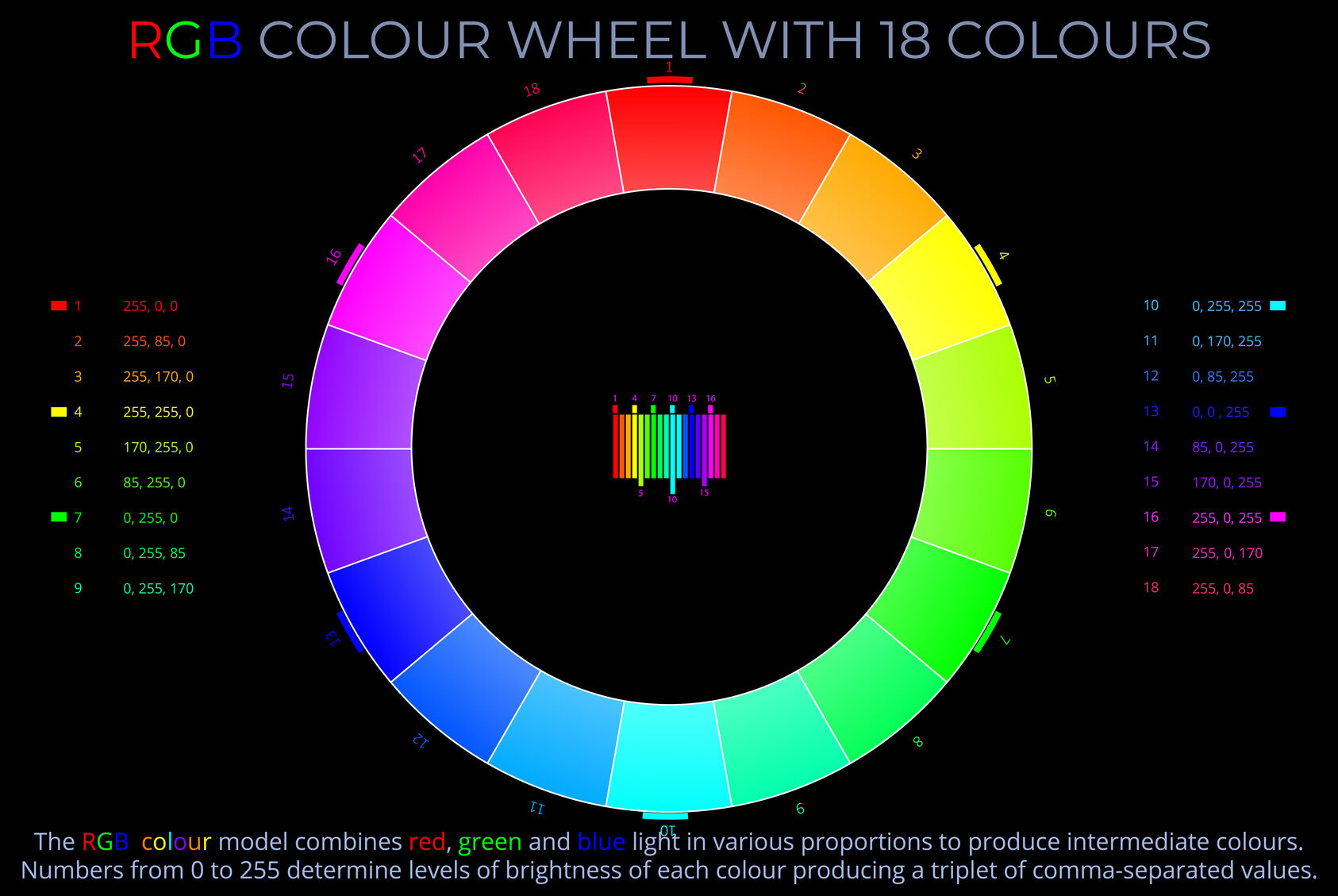

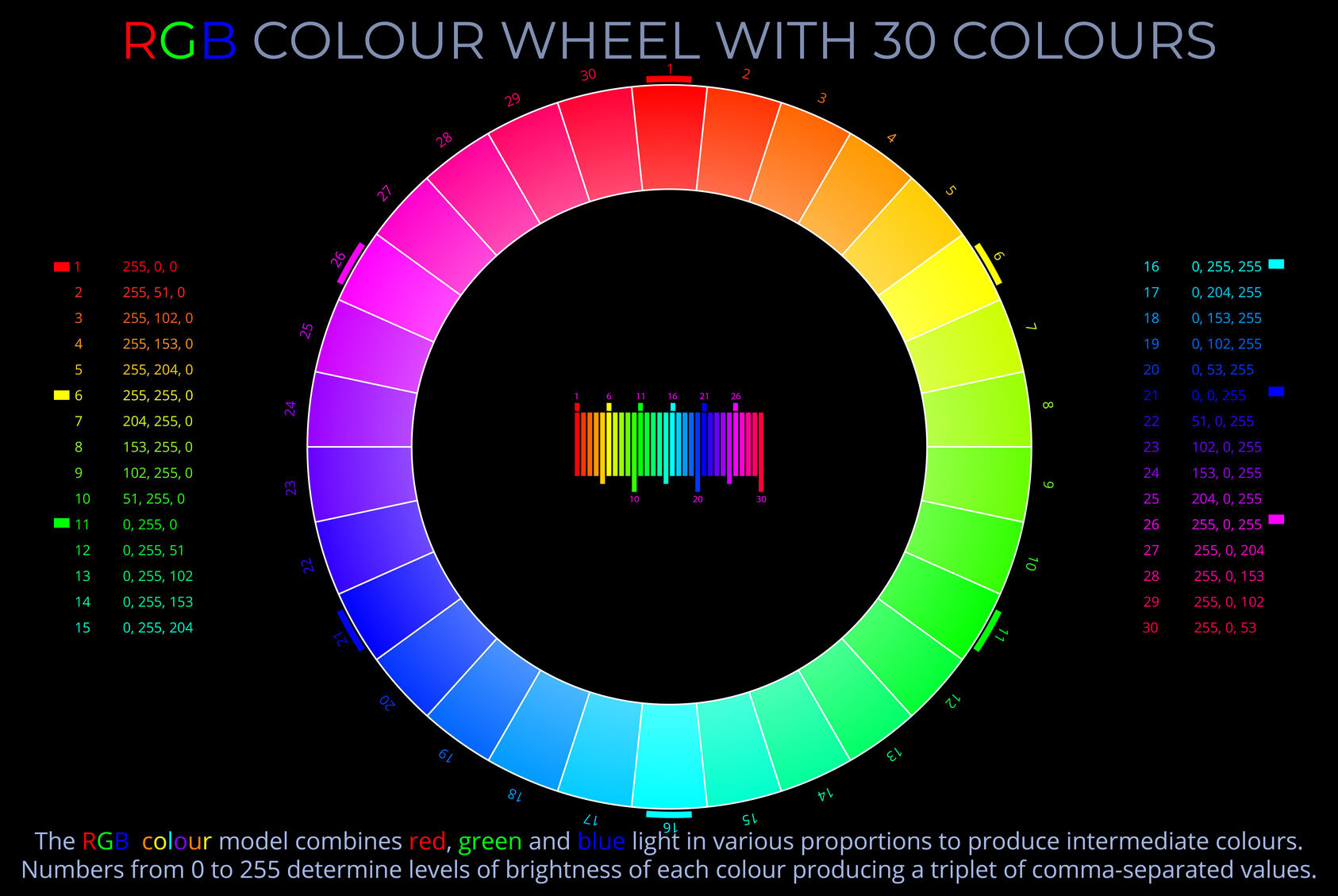

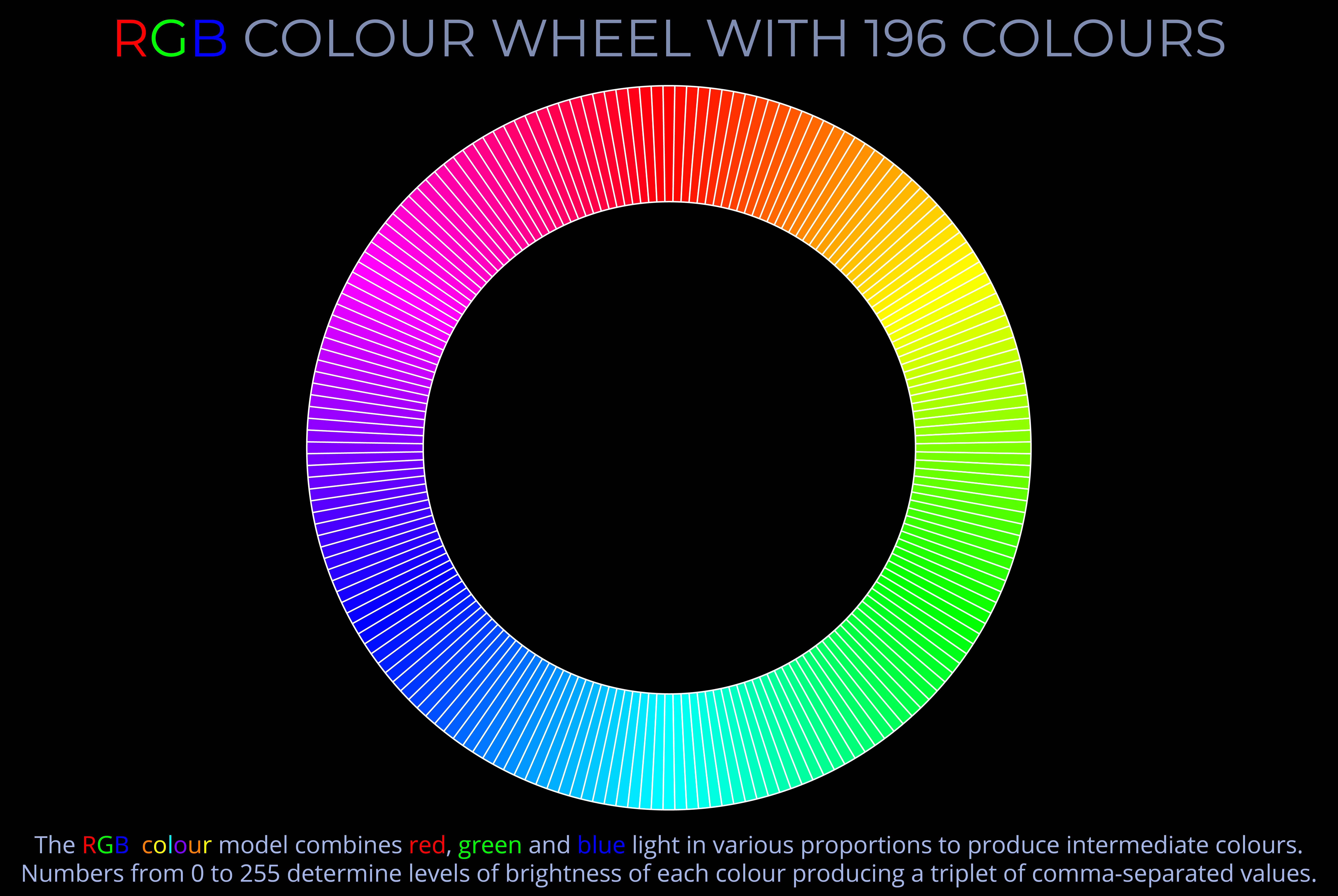

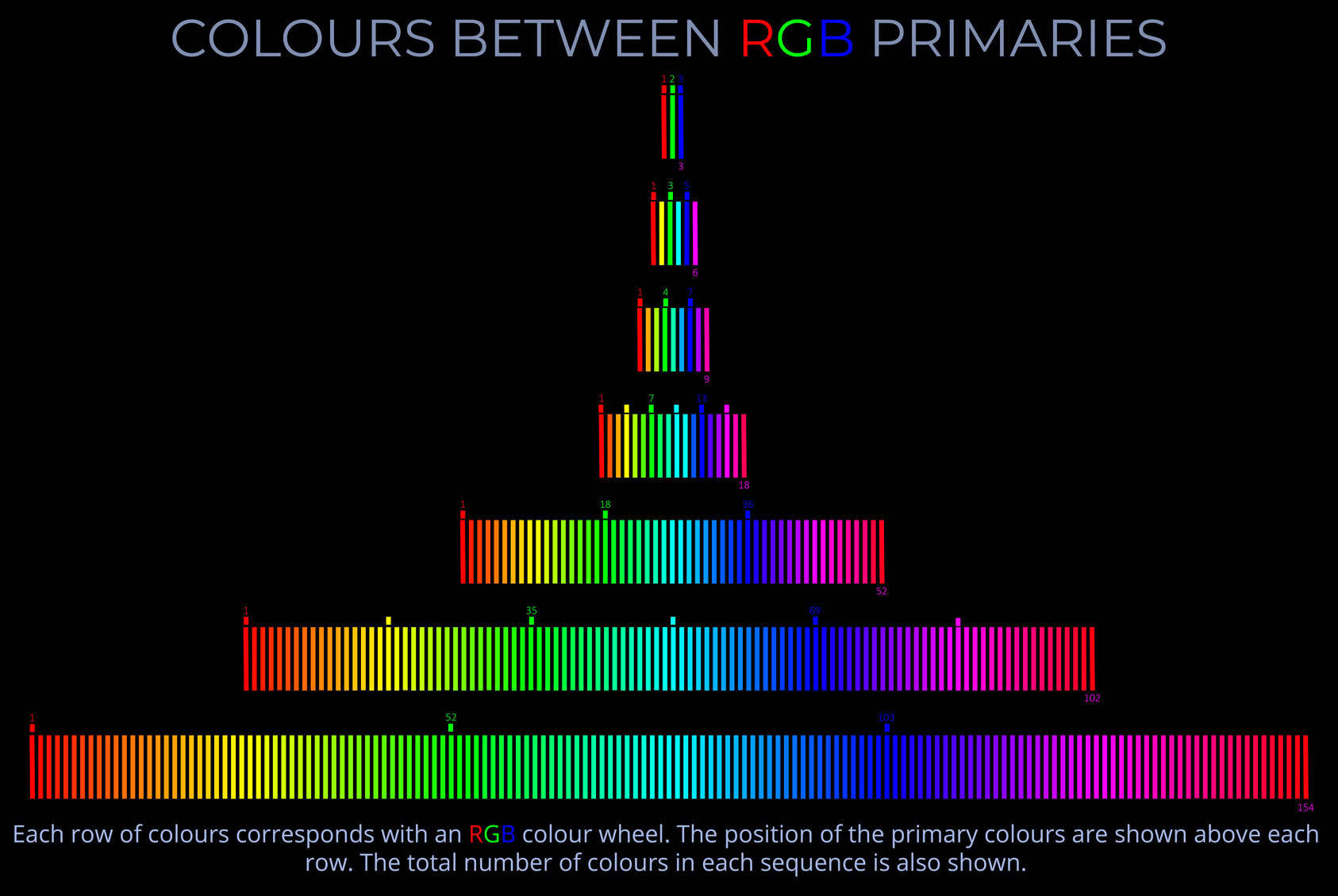

Analogous colours are colours that are very similar to one another and appear next to each other on a colour wheel.

- Analogous colours are colours with similar hues.

- An example of a set of analogous colours is red, reddish-orange, orange, and yellow-orange.

- An analogous colour scheme creates a rich appearance but is generally less vibrant than a colour scheme with contrasting colours.

- Increasing the number of segments on a colour wheel shows analogous colours more clearly because the gradation between adjacent hues becomes finer.

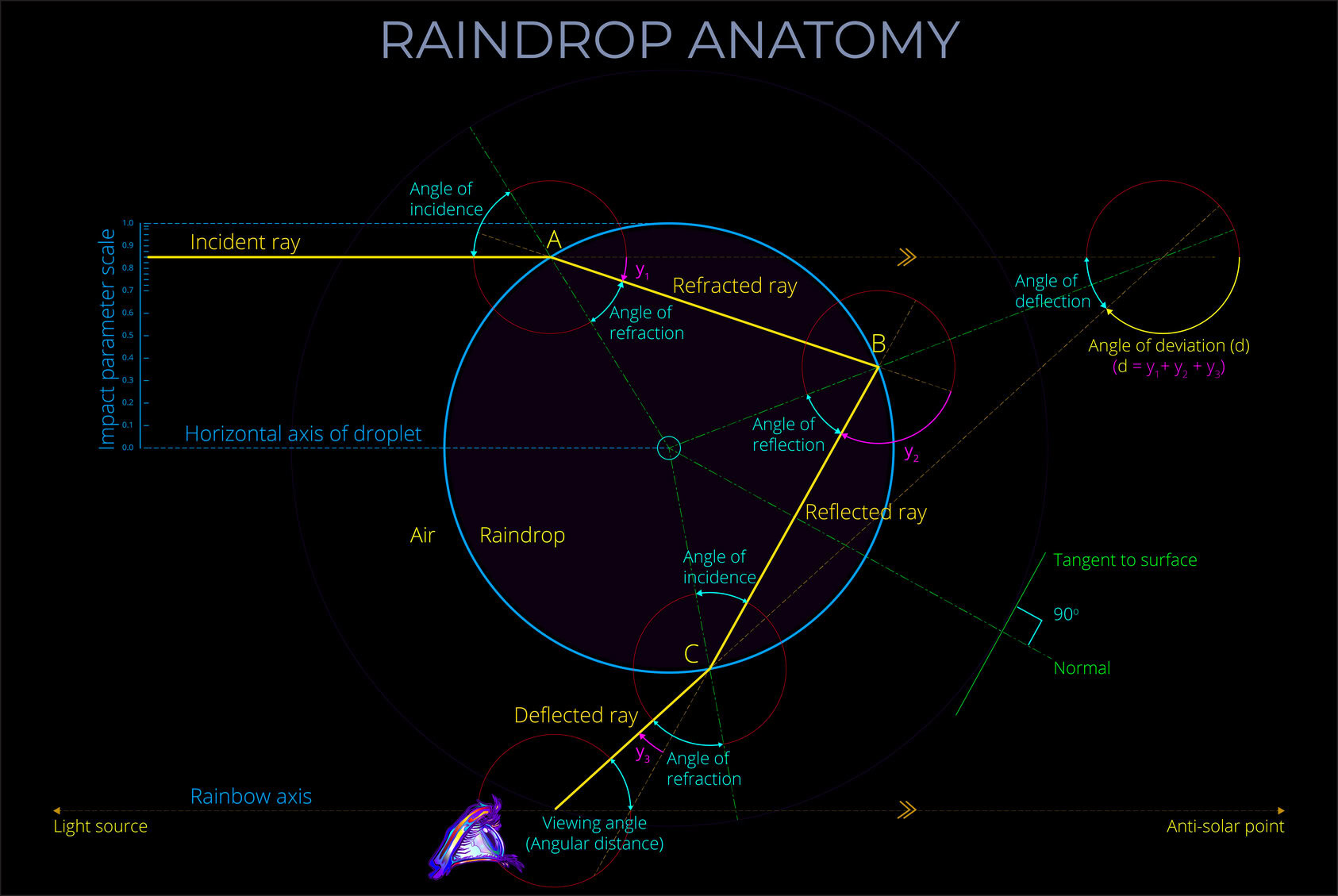

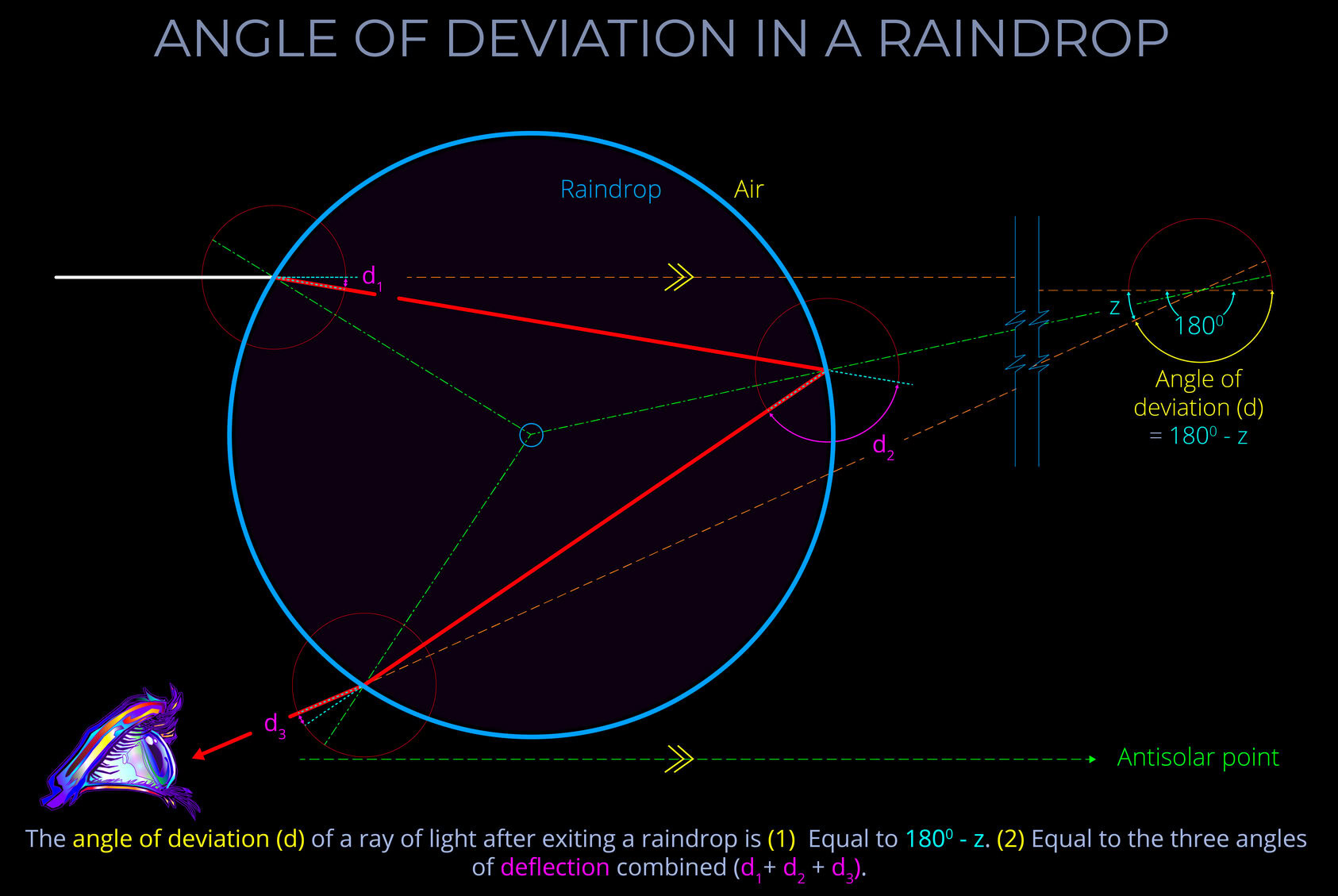

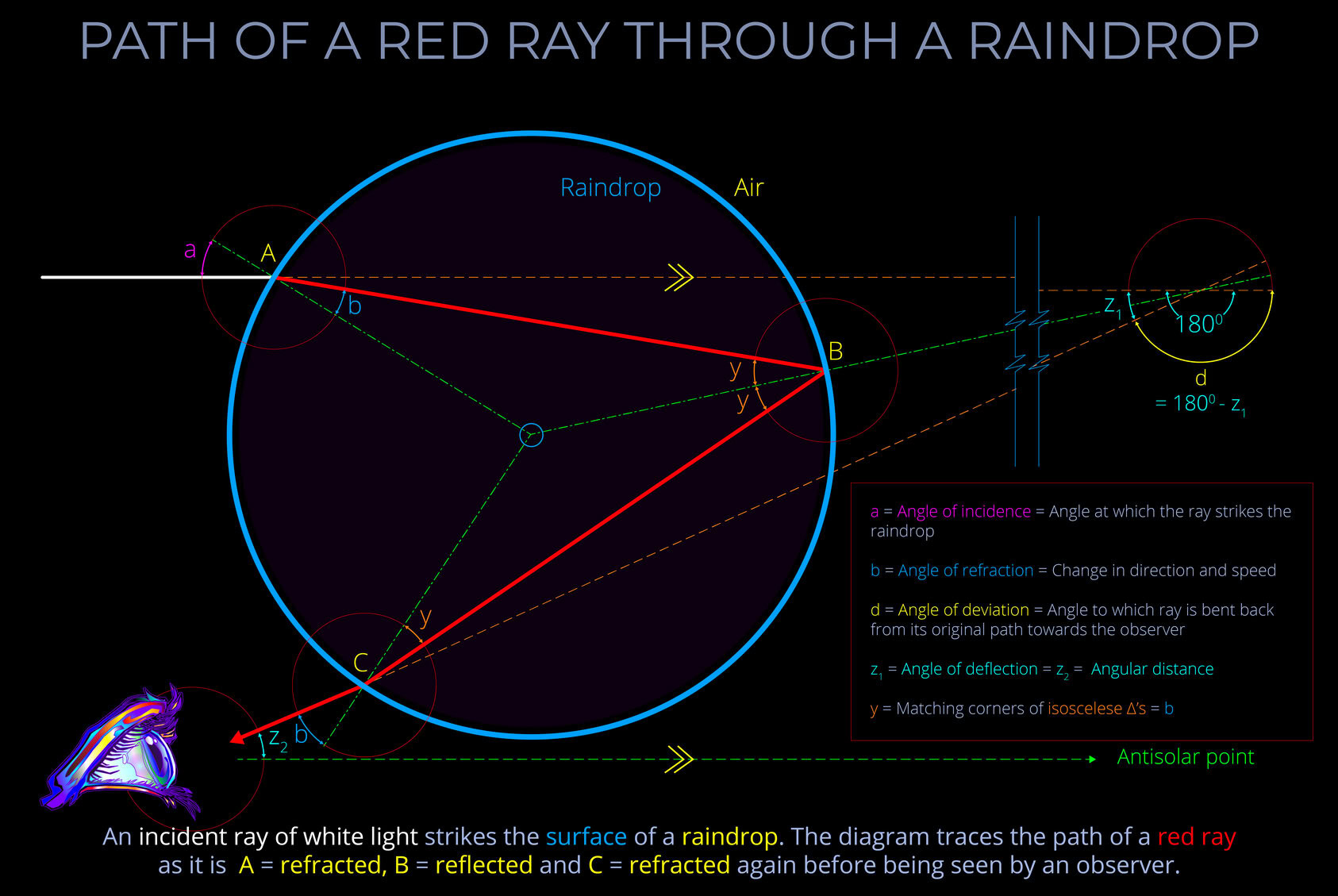

The angle of deflection measures the angle between the original path of a ray of incident light prior to striking a raindrop and the angle of deviation which measures the degree to which the ray is bent back on itself in the course of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

- The angle of deflection and the angle of deviation are always directly related to one another and together add up to 1800.

- The angle of deflection is equal to 1800 minus the angle of deviation. So clearly the angle of deviation is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deflection.

- In any particular example, the angle of deflection is always the same as the viewing angle because the incident rays of light that form a rainbow all approach on a trajectory running parallel with the rainbow axis.

Remember that:

- Any ray of light (stream of photons) travelling through empty space, unaffected by gravitational forces, travels in a straight line forever.

- When light travels from a vacuum or from one transparent medium into another, it undergoes refraction causing it to change both direction and speed.

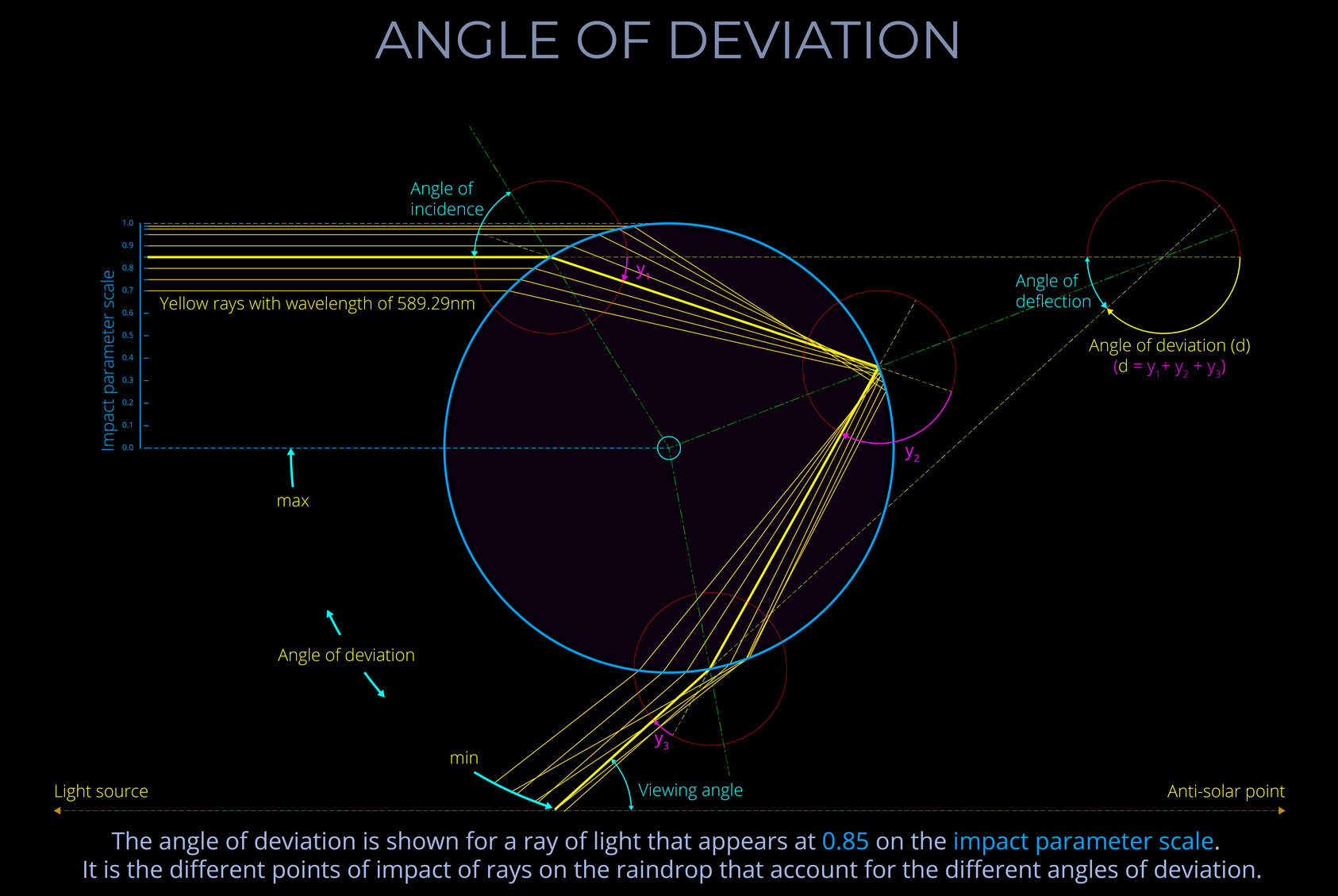

- The more a ray changes direction as it passes through a raindrop the smaller will be the angle of deflection.

- It is the optical properties of raindrops that determine the angle of deflection of incident light as it exits a raindrop.

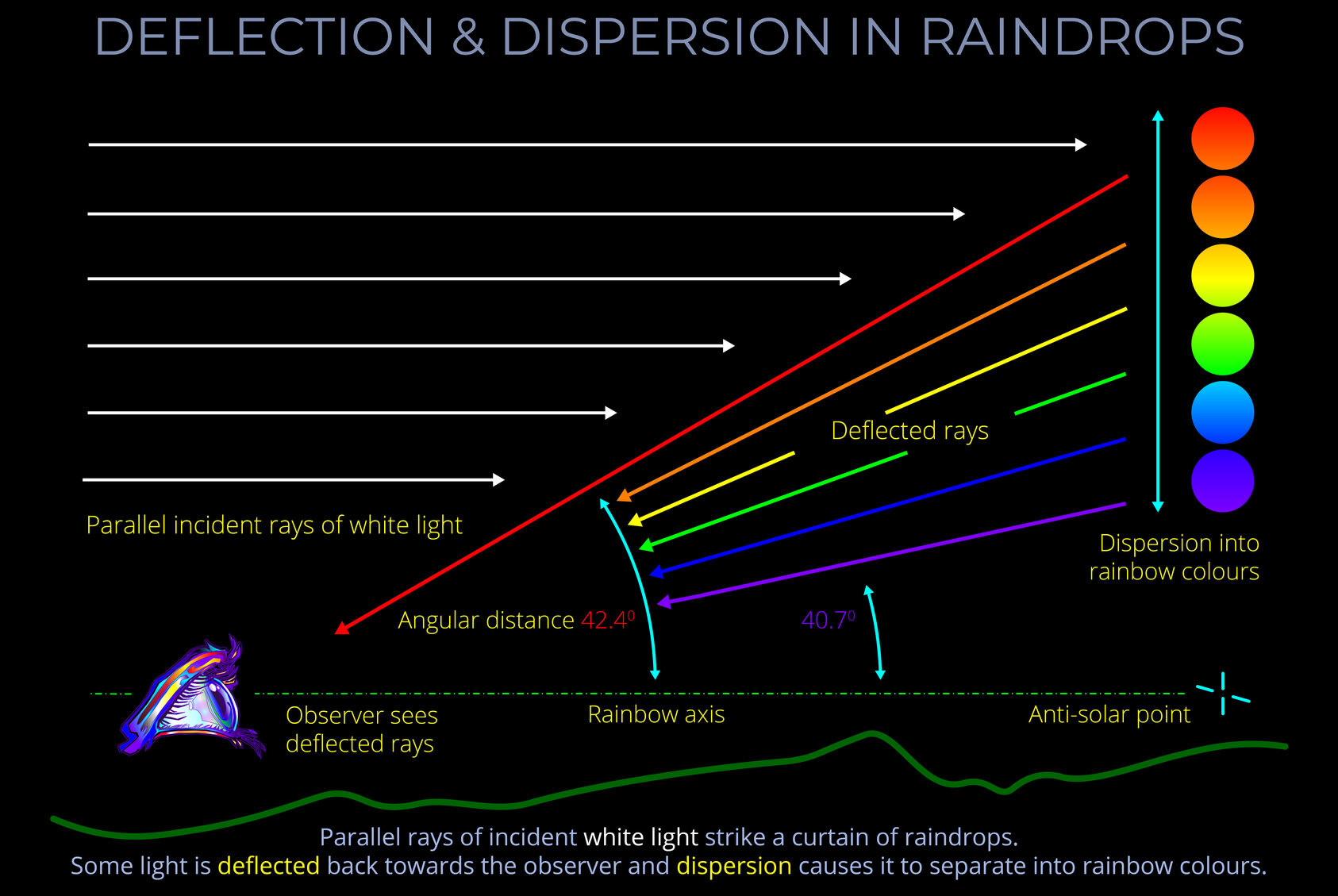

- It is the optical properties of raindrops that prevent any ray of visible light from exiting a primary raindrop at an angle of deflection larger than 42.70.

Now consider the following:

- For a single incident ray of light of a known wavelength striking a raindrop at a known angle:

- To appear in a primary rainbow it cannot exceed an angle of deflection of more than 42.70. This corresponds with the minimum angle of deviation.

- 42.70 is the angle of deflection that produces the appearance of red along the outside edge of a primary rainbow from the point of view of an observer.

- 1800 – 137.60 = 42.0 4 is the maximum angle of deflection for any ray of visible light if it is to appear within a primary rainbow.

- 1800 -139.30 = 40.70 is the angle of deflection for a ray that appears violet along the inside edge of a primary rainbow.

- Angles of deviation between 137.60 and 139.30 correspond with viewing angles and angles of deflection between 42.40 (red) and 40.70 (violet).

- An angle of deviation of 137.60 (so viewing angles of 42.40) corresponds with the appearance of red light with a wavelength of approx. 720 nm.

- The range of angles of deflection that create the impression of colour for an observer is not related to droplet size.

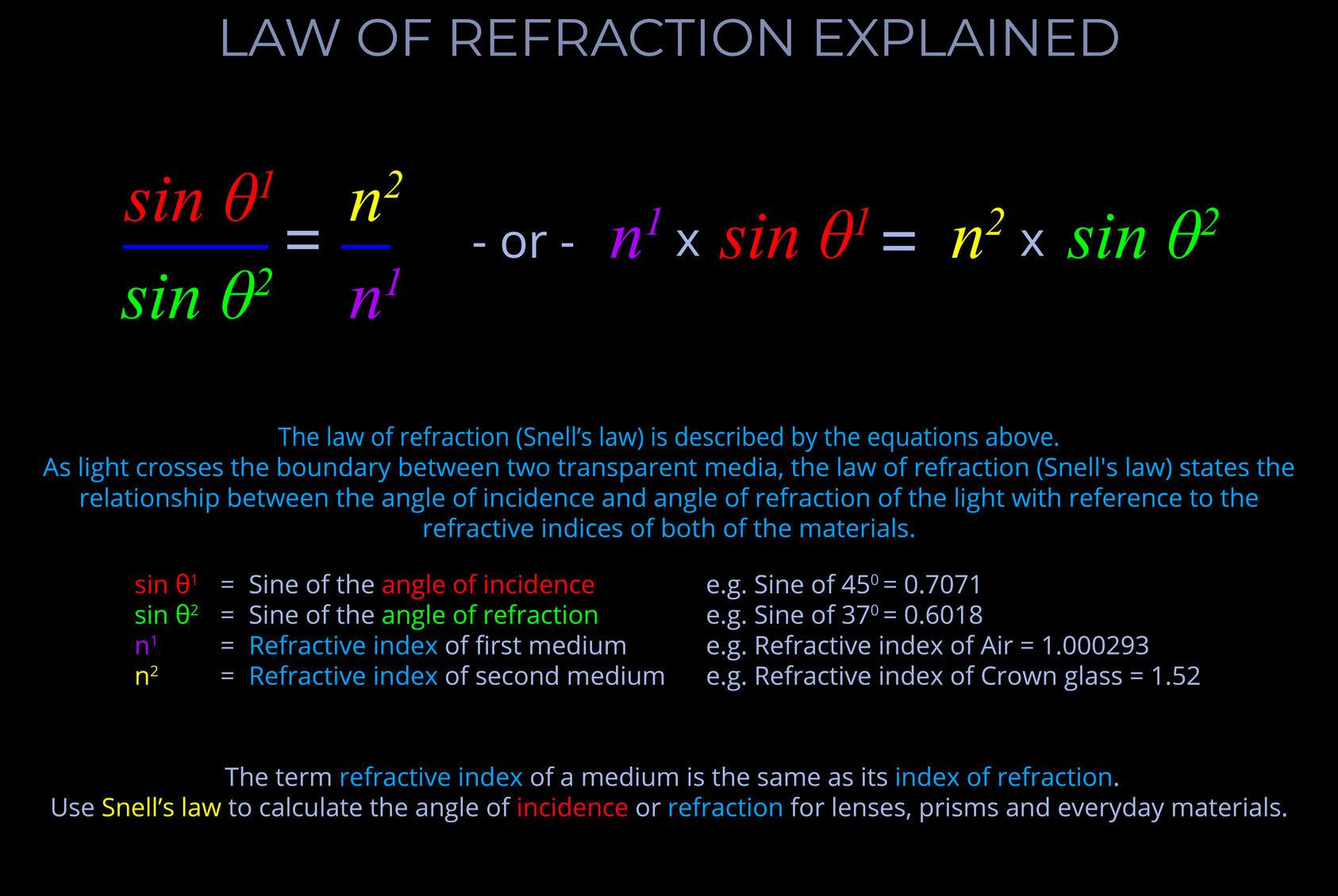

- The laws of refraction (Snell’s law) and reflection and the law of reflection can be used to calculate the angle of deviation of white light in a raindrop.

- The angle of deviation can be fine-tuned for any specific wavelength by fine adjustment of the refractive index.

Viewing angle, angular distance and angle of deflection

- The term viewing angle refers to the number of degrees through which an observer must move their eyes or turn their head to see a specific colour within the arcs of a rainbow.

- The term angular distance refers to the same measurement when shown in side elevation on a diagram.

- The angle of deflection measures the angle between the original path of a ray of incident light prior to striking a raindrop and the angle of deviation.

- The term rainbow ray refers to the path taken by the deflected ray that produces the most intense colour experience for any particular wavelength of light passing through a raindrop.

- The term angle of deviation measures the degree to which the path of a light ray is bent back by a raindrop in the course of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

- In any particular example of a ray of light passing through a raindrop, the angle of deviation and the angle of deflection are directly related to one another and together add up to 1800.

- The angle of deviation is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deflection. So clearly the angle of deflection is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deviation.

- In any particular example, the angle of deflection is always the same as the viewing angle because the incident rays of light that form a rainbow are all approaching on a trajectory running parallel with the rainbow axis.

When discussing the formation of rainbows, the angle of deflection measures the angle between the initial path of a light ray before it hits a raindrop, and the angle of deviation, which measures how much the ray bends back on itself in the course of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

- See this diagram for an explanation: Rainbow anatomy

- The angle of deflection and the angle of deviation are always directly related to one another and together add up to 180 degrees.

- The angle of deflection equals 180 degrees minus the angle of deviation. So, it’s clear the angle of deviation is always equal to 180 degrees minus the angle of deflection.

- In any particular case, the angle of deflection is always the same as the viewing angle because the incident rays of light that form a rainbow all follow paths that run parallel with the rainbow axis.

(1) The angle of deviation measures the angle between the direction of an incident ray and the direction of a refracted ray when light travels from one medium to another

(2) The angle of deviation measures the degree to which the path of light through a raindrop is altered in the course of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

About the angle of deviation (Raindrops)

- The angle of deviation is measured between the path of light incident to a raindrop and its path after it exits the raindrop back into air.

- In any particular example of light passing through a raindrop, the angle of deviation and the angle of deflection are directly related to one another and together add up to 1800.

- The angle of deviation is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deflection. So clearly the angle of deflection is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deviation.

- In any particular example, the angle of deflection is always the same as the viewing angle because the incident light that forms a rainbow, if thought of in terms of rays, is approaching on trajectories running parallel with the rainbow axis.

Remember that:

- Any ray of light (stream of photons) travelling through empty space, unaffected by gravitational forces, travels in a straight line forever.

- When light leaves a vacuum or travels from one transparent medium into another, it undergoes refraction causing it to change both direction and speed.

- The more a ray changes direction as it passes through a raindrop the greater will be its angle of deviation.

- Amongst the optical properties of air and water, absorption, reflection, refraction, and scattering of light are the most important.

- It is the optical properties of raindrops that determine the angle of deviation of incident light as it exits a raindrop.

- It is the optical properties of raindrops that prevent any ray of visible light from exiting a primary raindrop at an angle of deviation less than 137.60.

Now consider the following:

- For a single incident ray of light of a known wavelength striking a raindrop at a known angle:

- To appear in a primary rainbow it must reach an angle of deviation of at least 137.60 if it is to be visible to an observer.

- 137.60 is the angle of deviation that produces the appearance of red along the outside edge of a primary rainbow from the point of view of an observer.

- 137.60 is the minimum angle of deviation for any ray of visible light if it is to appear within a primary rainbow.

- 139.30 is the angle of deviation for a ray that appears violet along the inside edge of a primary rainbow.

- Angles of deviation between 137.60 and 139.30 correspond with viewing angles between 42.40 (red) and 40.70 (violet).

- For any raindrop to form part of a primary rainbow it must be between the viewing angles of 42.40 (red) and 40.70 (violet)

- An angle of deviation of 137.60 (so viewing angles of 42.40) corresponds with the appearance of red light with a wavelength of approx. 720 nm.

- The range of angles of deviation that create the impression of colour for an observer is not related to droplet size.

- The laws of refraction (Snell’s law) and reflection can be used to calculate the angle of deviation of white light in a raindrop.

- The angle of deviation can be fine-tuned for any specific wavelength by making a small adjustment to the refractive index of water.

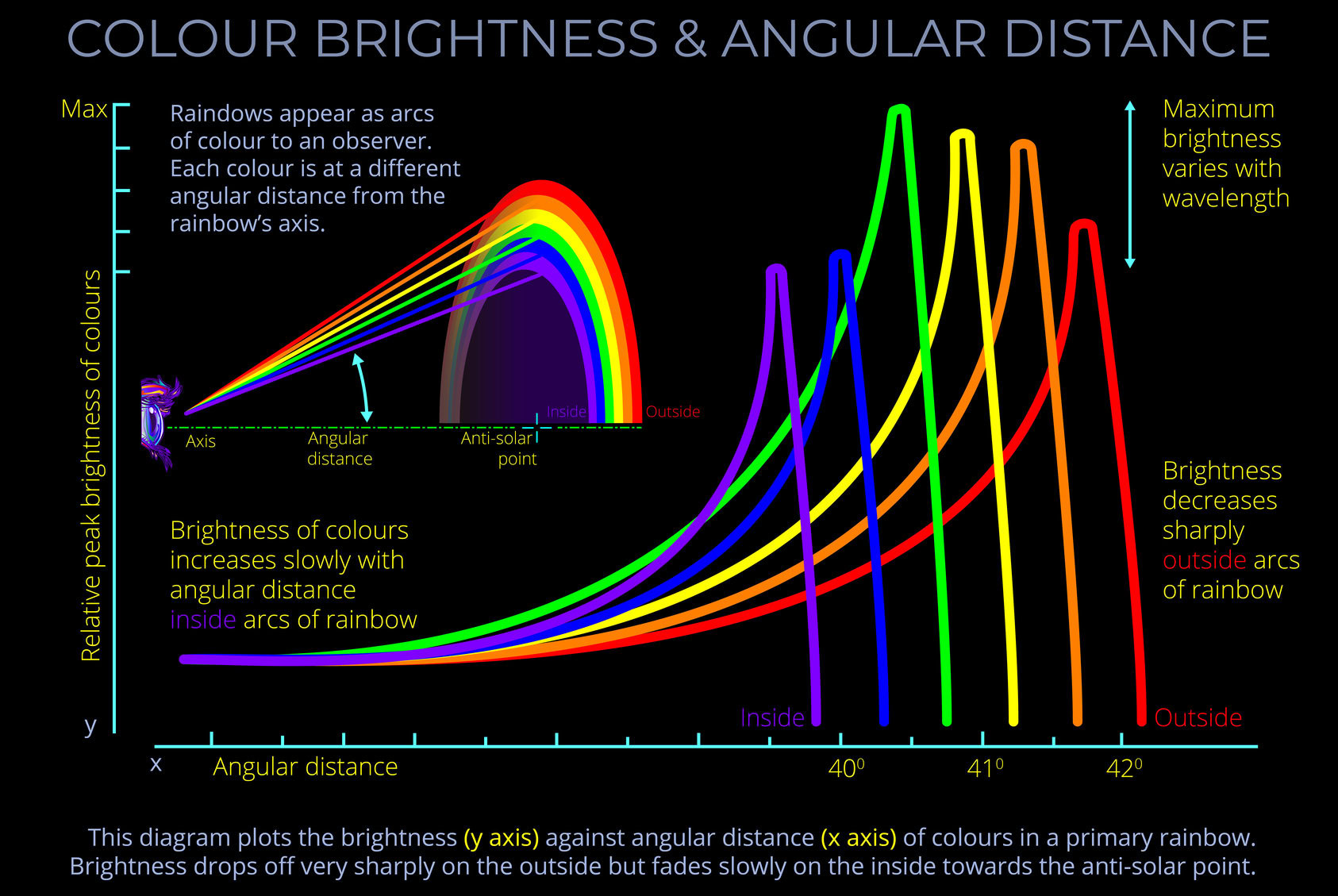

Minimum angle of deviation

- The optical properties of an idealised spherical raindrop mean that no light of any specific wavelength can deviate less than its minimum angle of deviation.

- The minimum angle of deviation for red light with a wavelength of approx. 720 nm is always 137.60 but similar rays with other points of impact can deviate up to a maximum of 1800.

- Imagine a falling raindrop:

- At a specific moment, the droplet is at an angle of 500 from the rainbow axis as seen from the point of view of an observer. This corresponds with an angle of deviation of 1300 which is insufficient to be visible to an observer.

- A moment later the droplet is at an angle of 42.40 which is the viewing angle for red in a primary rainbow so the droplet becomes visible to the observer.

- 42.40 corresponds with the rainbow angle for light with a wavelength of 720 nm, so at this moment the droplet appears red at maximum intensity.

- As the droplet continues to fall, the minimum angle of deviation for red is passed and so that colour fades just as the minimum angle of deviation for orange arrives. For a second the same droplet now appears intensely orange.

- The sequence repeats for yellow, green, blue and then violet at which point the viewing angle drops below 40.70. A moment later, it briefly produces ultra-violet light.

- As soon as the minimum angle of deviation for violet is exceeded, increasing towards 1800, it no longer forms part of the arcs of colour seen by an observer, but continues to scatter light into the area between the bow and anti-solar point.

By way of summary

- Raindrops do not reflect light at an angle less than its minimum angle of deviation.

- The minimum angle of deviation for any wavelength of visible light is never less than 137.60 whilst the maximum is always 1800.

- When the angle of deviation is 1800, the angles or refraction (on the entry and exit of a raindrop) = 00 and the angle of reflection = 1800.

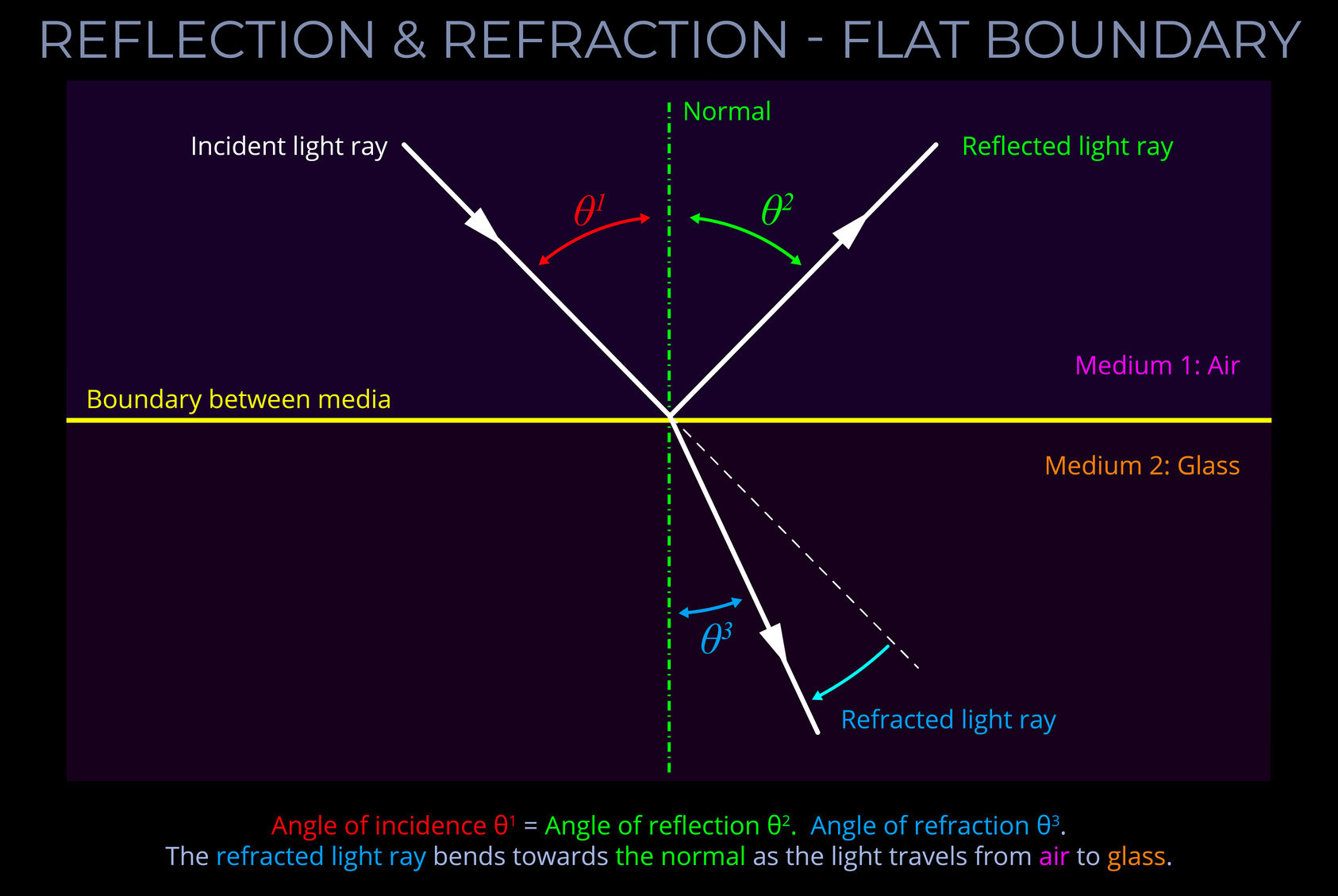

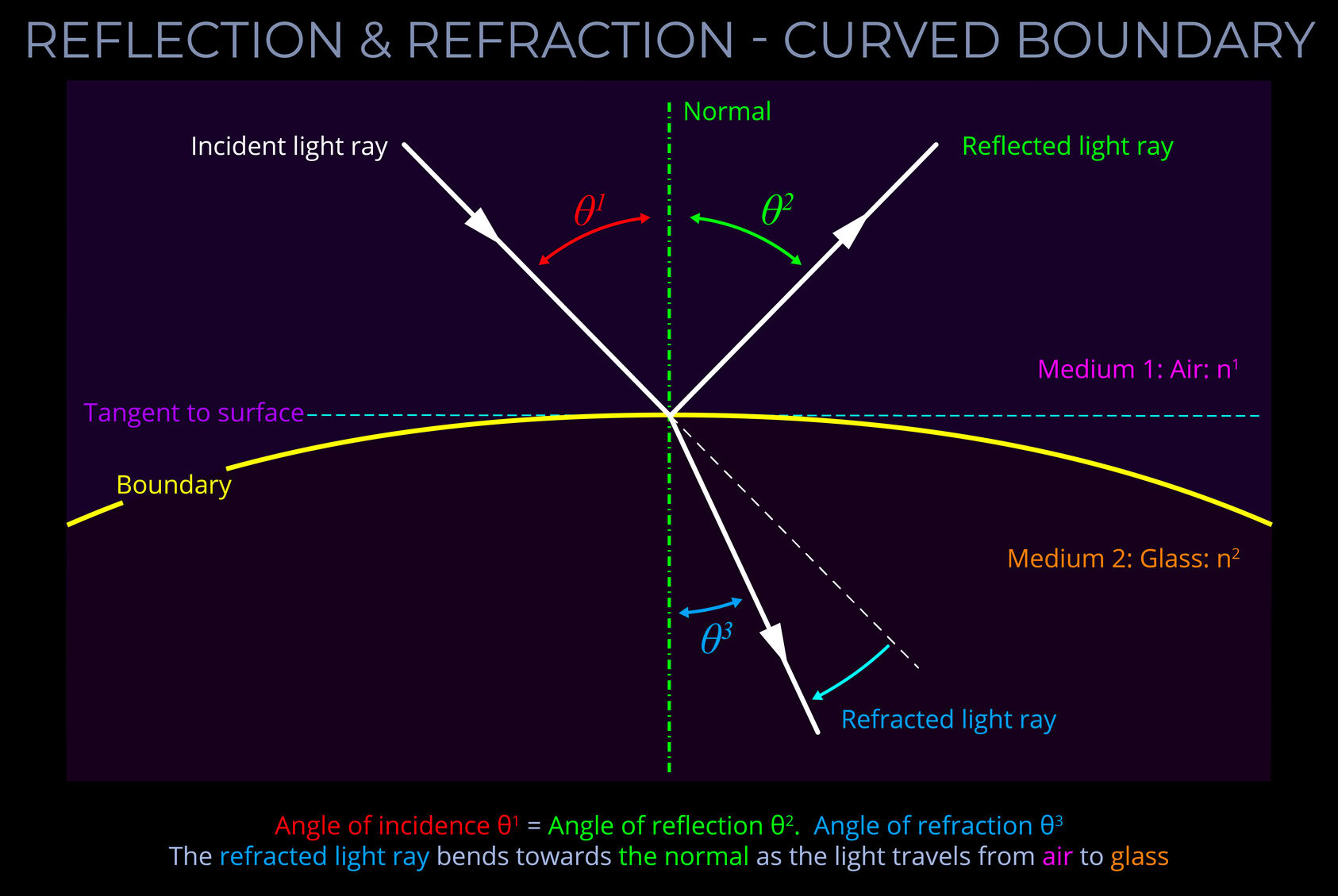

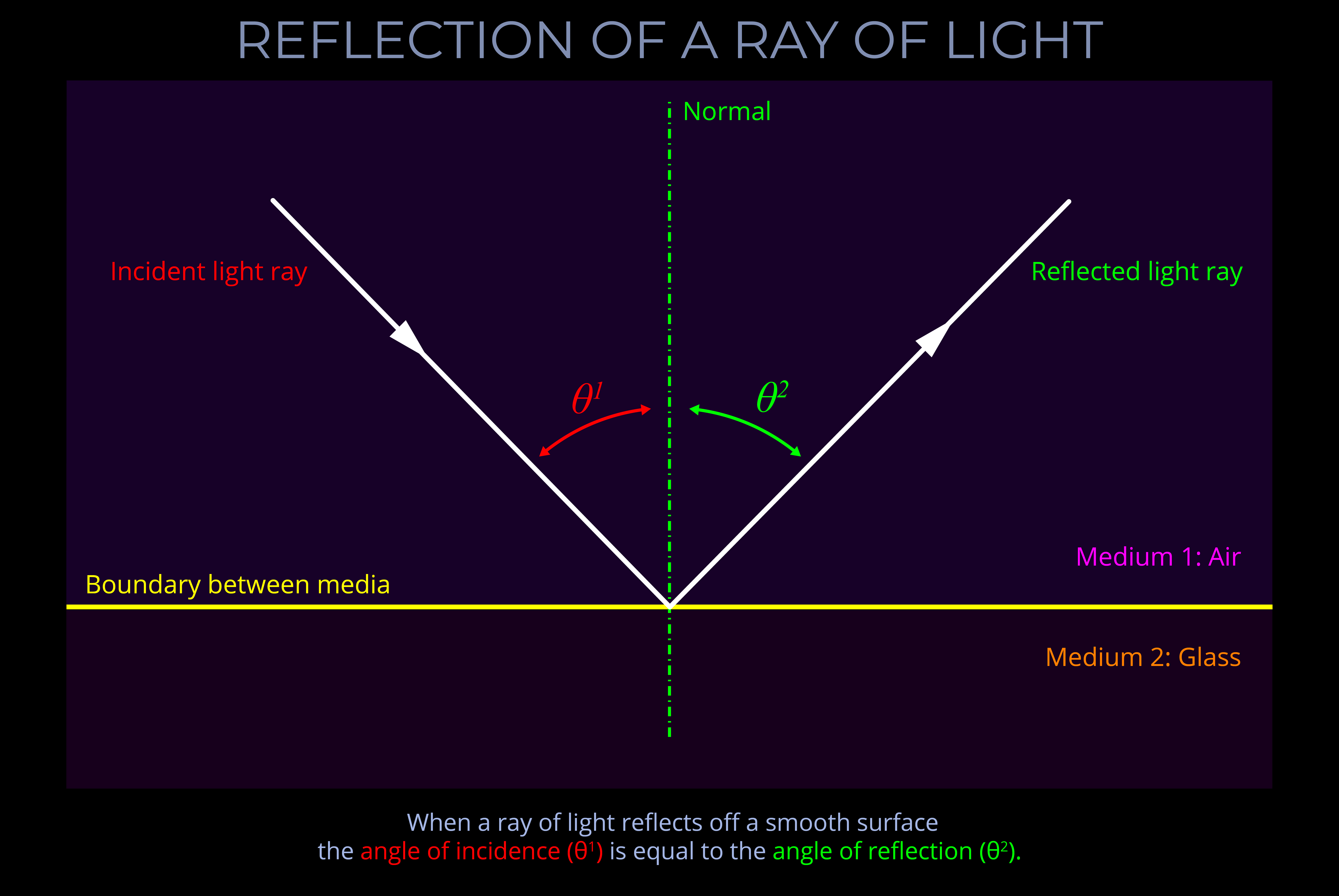

The angle of incidence measures the angle at which incoming light strikes a surface.

- The angle of incidence is measured between a ray of incoming light and an imaginary line called the normal.

- See this diagram for an explanation: Reflection of a ray of light

- In optics, the normal is a line drawn on a ray diagram perpendicular to, so at a right angle to (900), the boundary between two media.

- If the boundary between the media is curved, then the normal is drawn at a tangent to the boundary.

The angle of reflection measures the angle at which reflected light bounces off a surface.

- The angle of reflection is measured between a ray of light which has been reflected off a surface and an imaginary line called the normal.

- See this diagram for an explanation: Reflection of a ray of light

- In optics, the normal is a line drawn on a ray diagram perpendicular to, so at a right angle to (900), the boundary between two media.

- If the boundary between the media is curved then the normal is drawn perpendicular to the boundary.

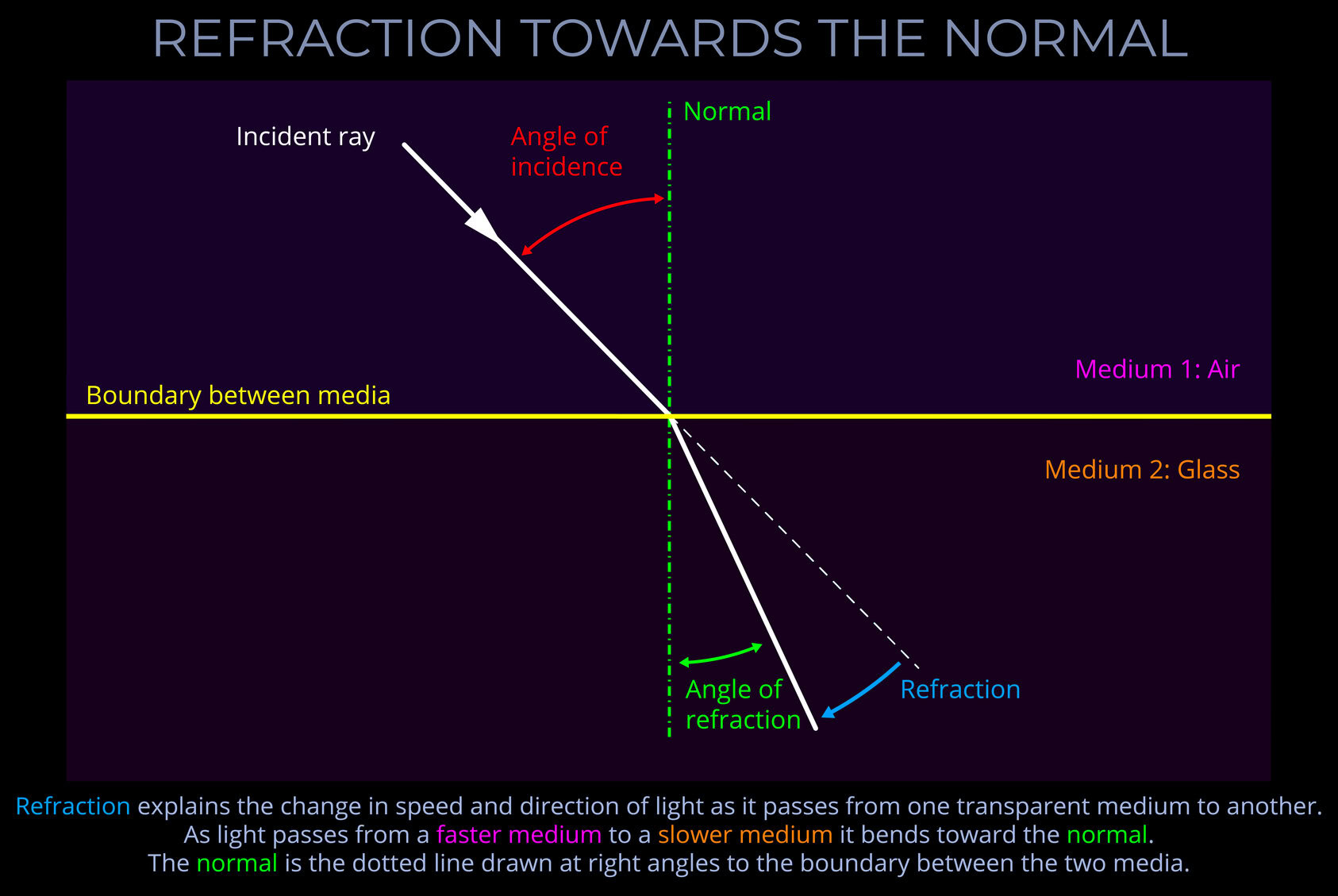

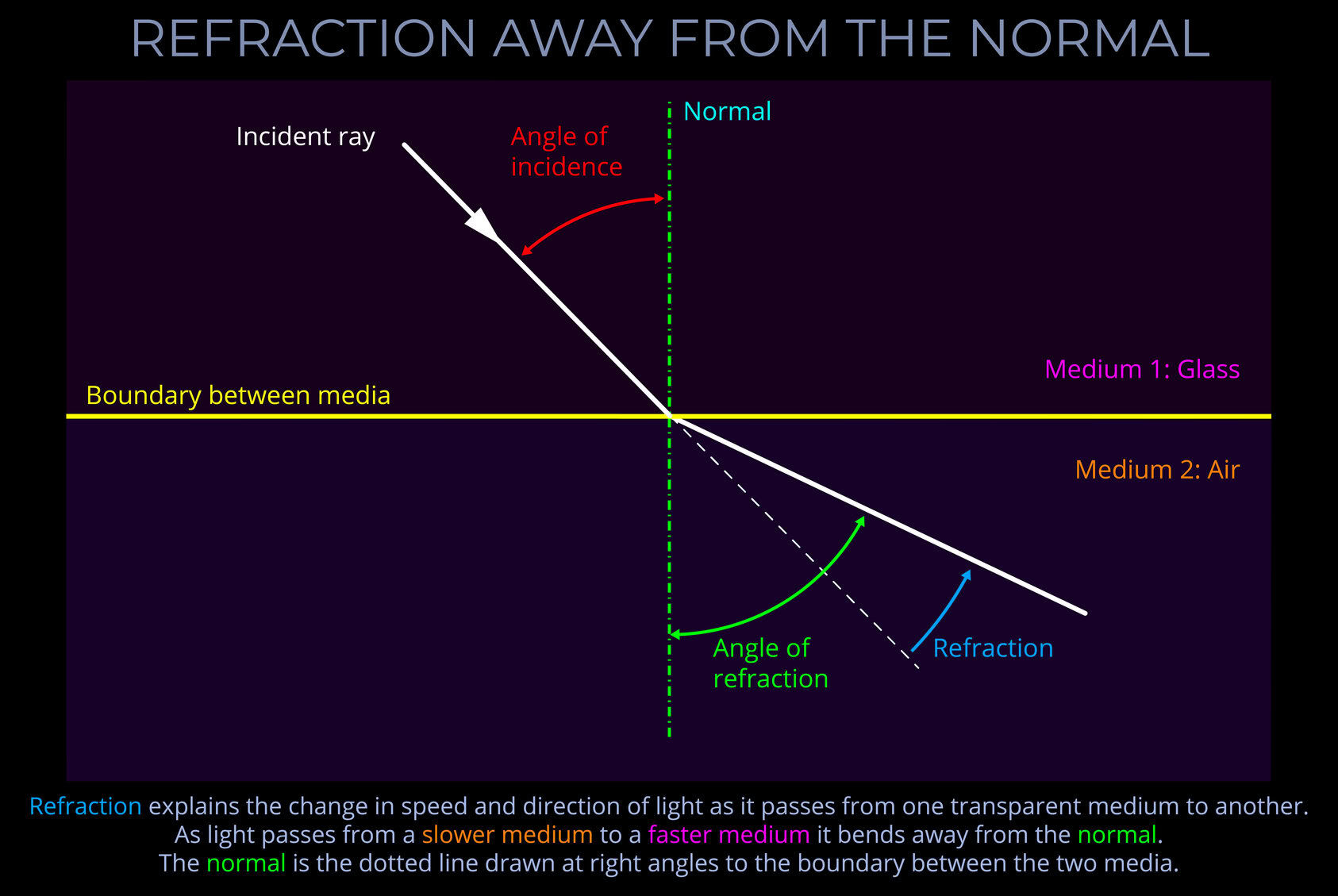

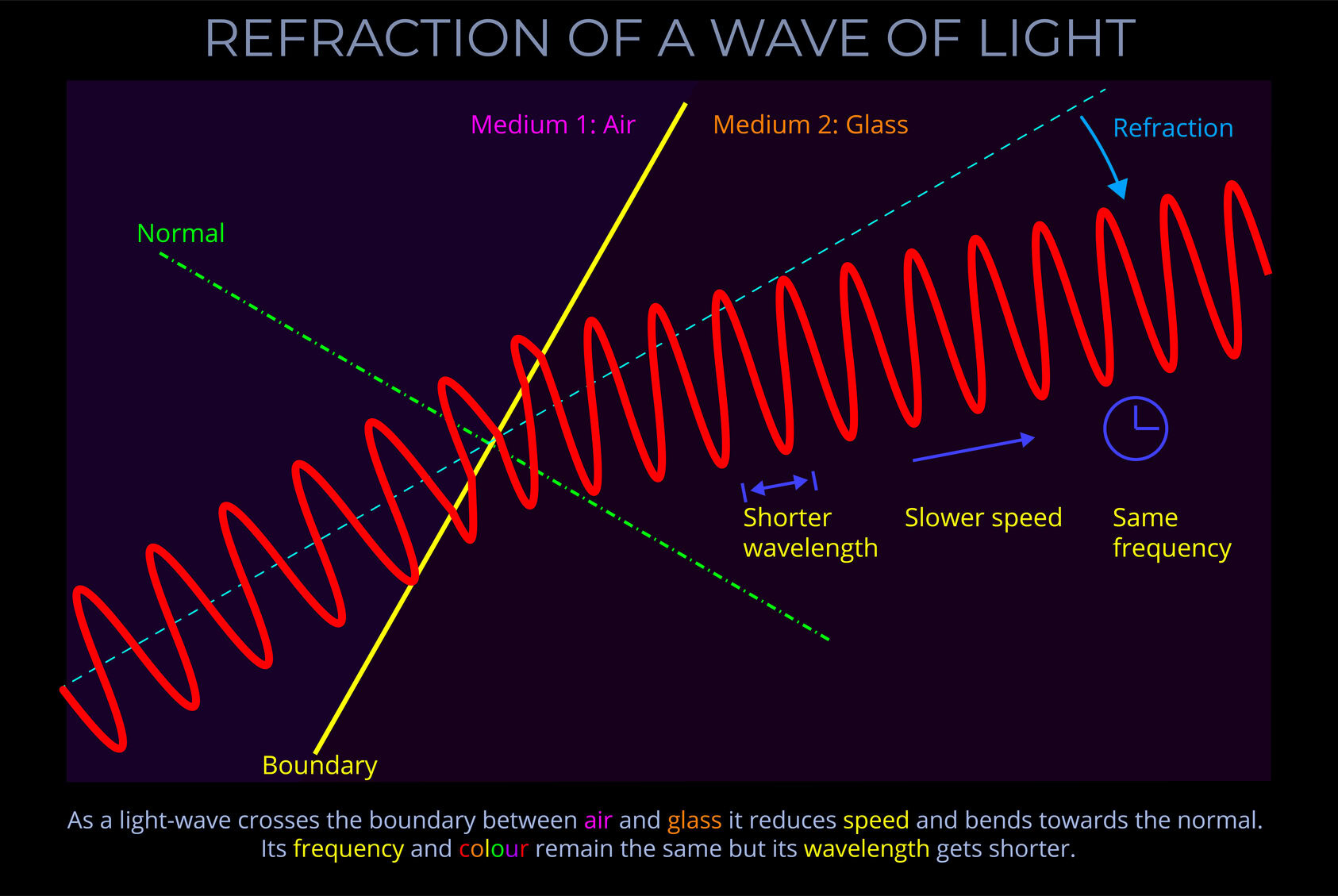

The angle of refraction measures the angle to which light bends as it passes across the boundary between different media.

- The angle of refraction is measured between a ray of light and an imaginary line called the normal.

- In optics, the normal is a line drawn on a ray diagram perpendicular to, so at a right angle to (900), the boundary between two media.

- See this diagram for an explanation: Refraction of a ray of light

- If the boundary between the media is curved, the normal is drawn perpendicular to the boundary.

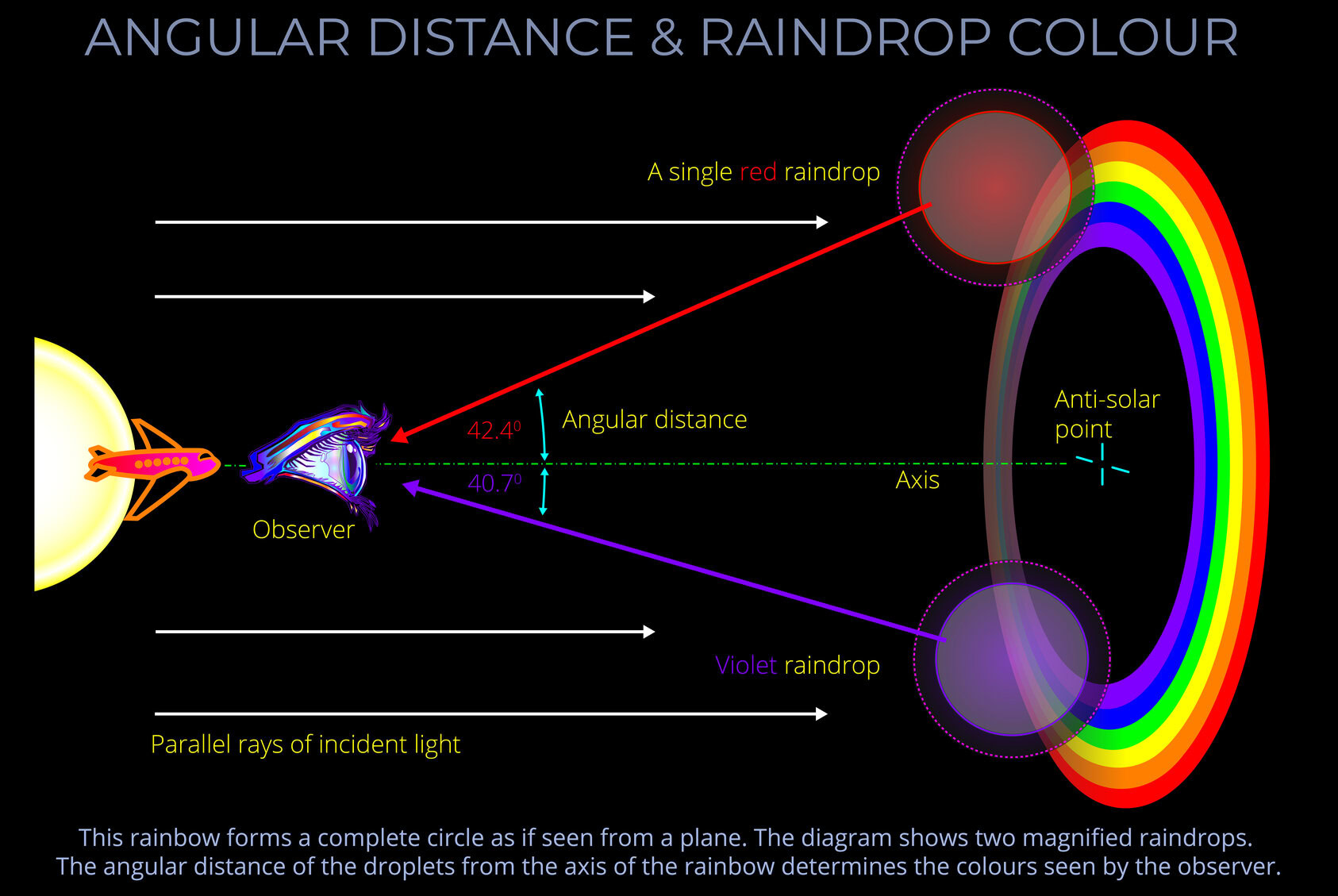

Angular distance is the angle between the rainbow axis and the direction in which an observer must look to see a specific colour within the arcs of a rainbow.

- Angular distance, viewing angle and angle of deflection all produce the same value measured in degrees.

- Angular distance is a measurement on a ray-tracing diagram that represents the Sun, an observer and a rainbow in side elevation.

- Think of angular distance as an angle between the centre of a rainbow and its coloured arcs with red at 42.40 and violet at 40.70.

- Angular distances for different colours are constants determined by the laws of refraction and reflection.

- The elevation of the Sun, the location of the observer and exactly where rain is falling are all variables that determine where a rainbow will appear to an observer.

- The coloured arcs of a rainbow form the circumference of circles (discs or cones) and share a common centre.

- The angular distance to any specific colour is the same whatever point is selected on the circumference.

- The angular distance for any observed colour in a primary bow is between 42.40 and violet at 40.70.

- The angular distance for any observed colour in a secondary bow is between 53.40 and 50.40 from its centre.

- The angular distance can be calculated for any specific colour visible within a rainbow.

- Considered from an observer’s viewpoint, it is clear that all incident rays seen by an observer run parallel with each other as they approach a raindrop.

- Most of the observable incident rays that strike a raindrop follow paths that place them outside the range of possible viewing angles. The unobserved rays are all deflected towards the centre of a rainbow.

Viewing angle, angular distance and angle of deflection

- The term viewing angle refers to the number of degrees through which an observer must move their eyes or turn their head to see a specific colour within the arcs of a rainbow.

- The term angular distance refers to the same measurement when shown in side elevation on a diagram.

- The angle of deflection measures the degree to which a ray striking a raindrop is bent back on itself in the process of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

- The term rainbow ray refers to the path taken by the deflected ray that produces the most intense colour experience for any particular wavelength of light passing through a raindrop.

- The term angle of deviation measures the degree to which the path of a light ray is bent back by a raindrop in the course of refraction and reflection towards an observer.

- In any particular example of a ray of light passing through a raindrop, the angle of deviation and the angle of deflection are directly related to one another and together add up to 1800.

- The angle of deviation is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deflection. So clearly the angle of deflection is always equal to 1800 minus the angle of deviation.

- In any particular example, the angle of deflection is always the same as the viewing angle because the incident rays of light that form a rainbow are all approaching on a trajectory running parallel with the rainbow axis.

When discussing rainbows, angular distance is the angle between the line from the observer to the centre of the rainbow (rainbow axis) and the line from the observer to a specific colour within the arc of a rainbow.

- See this diagram for an explanation: Angular distance & Raindrop colour

- Angular distance is one of the angles measured on a ray-tracing diagram that illustrates the sun, an observer, and a rainbow from a side view.

- Think of angular distance as the angle between the line to the centre of a rainbow down which an observer looks and the line to a specific colour in its arc. The red light is deviated by about 42.4° and violet light by about 40.7°.

On a sunny day, if you stand with the Sun at your back and look at the ground, the shadow of your head will align with the antisolar point.

- The antisolar point is the position directly opposite the Sun, around which the arcs of a rainbow appear. An imaginary straight line can always be drawn that passes through the Sun, the eyes of an observer, and the antisolar point, which is the geometric centre of a rainbow.

- This concept corresponds with what an observer sees in real life: the idea that a rainbow has a center. From a side view, the centre of a rainbow is called the antisolar point, so named because it is opposite the Sun relative to the observer’s position.

- Unless observed from the air, the antisolar point is always below the horizon. Both primary and secondary rainbows share the same antisolar point, as do higher-order bows, such as fifth and sixth-order rainbows.