Intensity measures the amount of light energy passing through a unit area perpendicular to the direction of light propagation.

- Intensity measures the amount of energy carried by a light wave or stream of photons.

- When light is modelled as a wave, intensity is proportional to the square of the amplitude.

- When light is modelled as a particle, intensity is proportional to the number of photons present at any given point in time.

- The intensity of light falls off as the inverse square of the distance from a point light source increases.

- Light intensity at any given distance from a light source is directly related to the power of the light source and the distance from the source.

- The power of a light source describes the rate at which energy is emitted and is measured in watts.

- The intensity of light is measured in watts per square meter (W/m²) and is also commonly expressed in lux (lx).

Light interference occurs when two or more light waves interact with one another, resulting in a combination of their amplitudes. The resulting wave may increase or decrease in strength.

- A simple form of interference takes place when two plane waves of the same frequency meet at an angle and combine.

- Light interference is often observed as interference patterns, such as seen in supernumerary rainbows.

- Interference patterns are produced when the energy of waves combines constructively or destructively. For example, waves on a pond can create interference patterns.

- Constructive interference occurs when the crest of one wave meets the crest of another wave of the same frequency at the same point. The resulting wave is the sum of the amplitudes of the original waves.

- Destructive interference occurs when the trough of one wave meets the crest of another wave. The resulting wave is the difference between the amplitudes of the original waves.

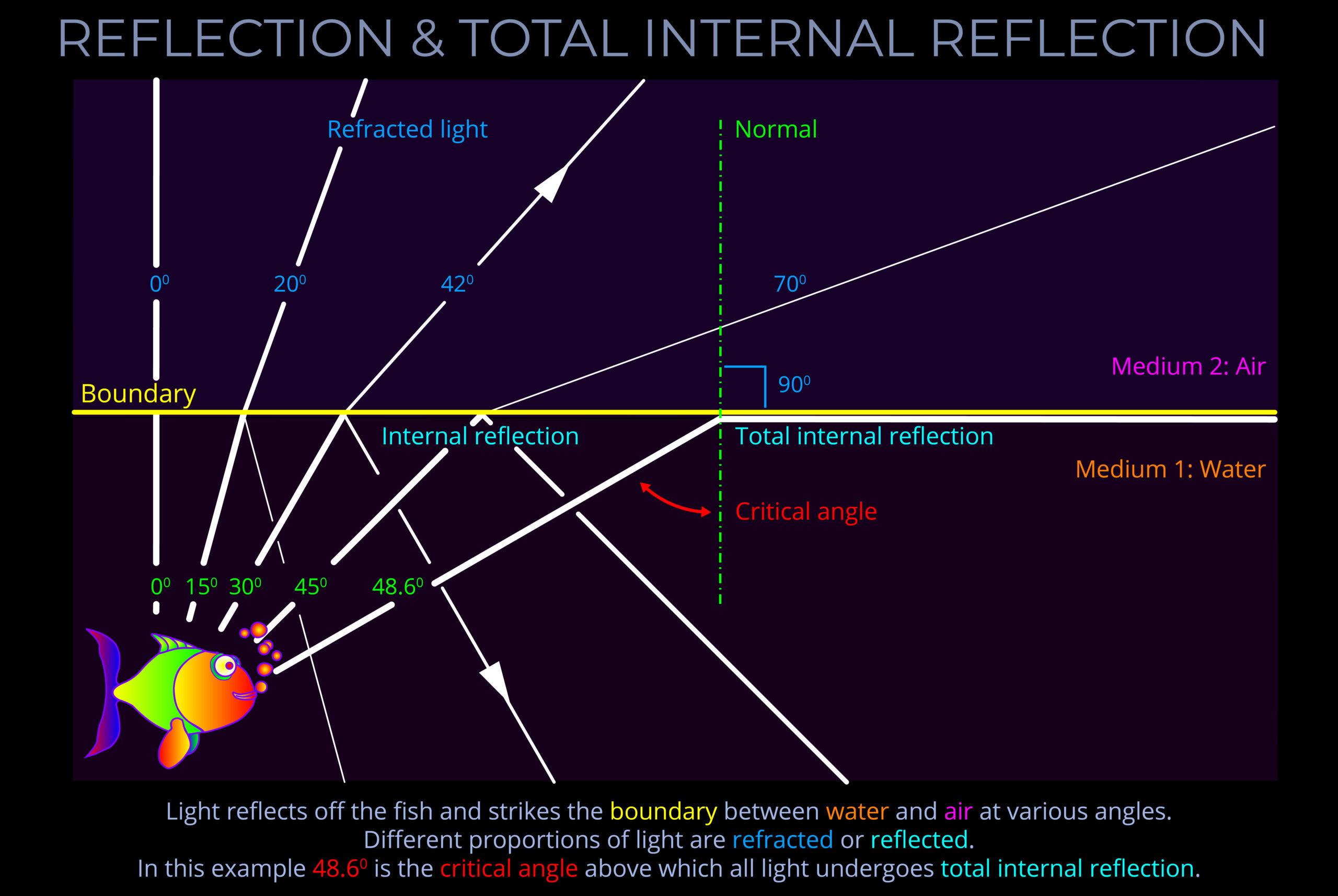

Internal reflection occurs when light travelling through a medium, such as water or glass, reaches the boundary with another medium, like air, and a portion of the light reflects back into the original medium. This happens regardless of the angle of incidence, as long as the light encounters the boundary between the two media.

- Internal reflection is a common phenomenon not only for visible light but for all types of electromagnetic radiation. For internal reflection to occur, the refractive index of the second medium must be lower than that of the first medium. This means internal reflection happens when light moves from a denser medium, such as water or glass, to a less dense medium, like air, but not when light moves from air to glass or water.

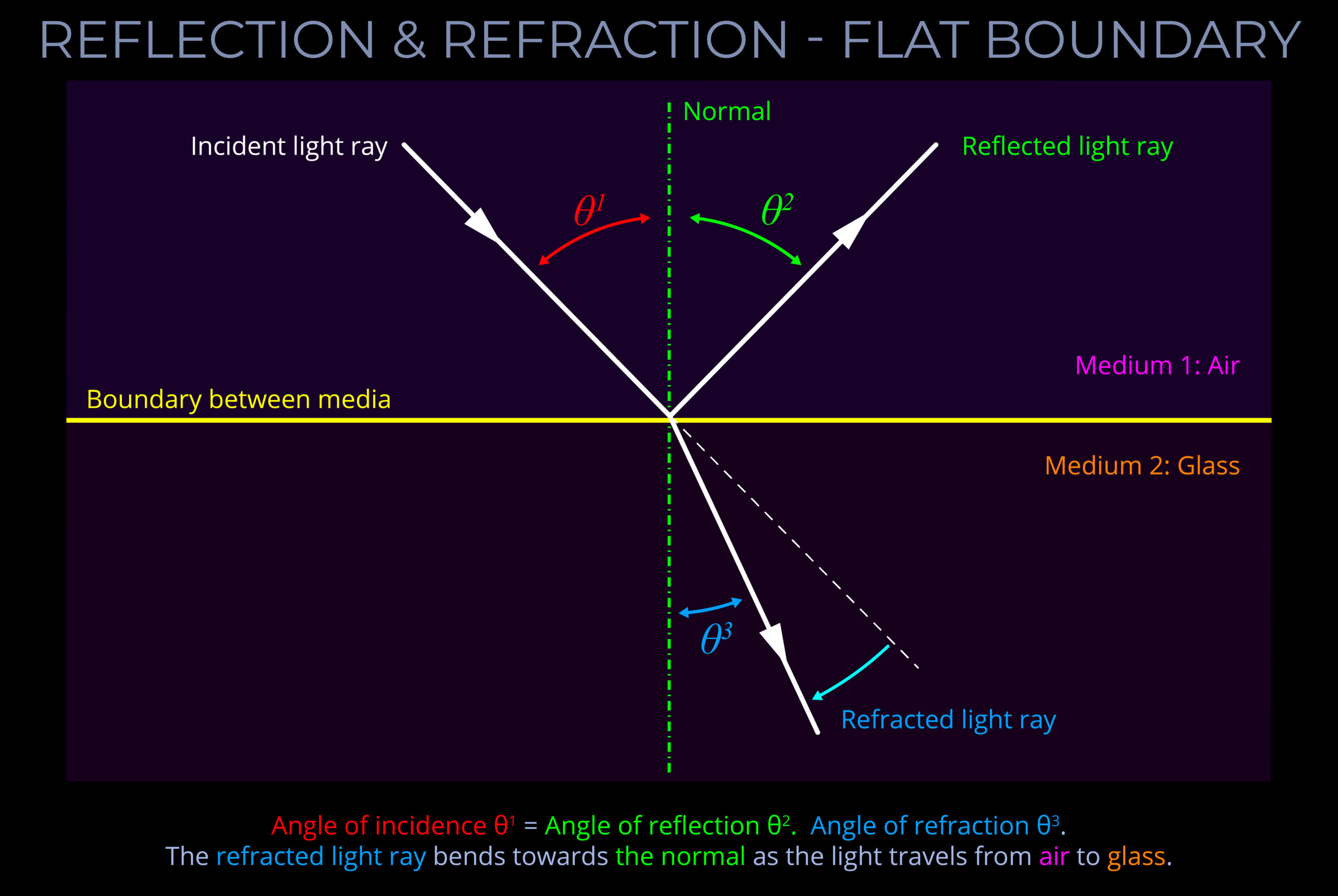

- In everyday situations, light is typically both refracted and reflected at the boundary between water or glass and air, often due to irregularities on the surface. If the angle at which light strikes this boundary is less than the critical angle, the light is refracted as it crosses into the second medium.

- When light strikes the boundary exactly at the critical angle, it neither fully reflects nor refracts but travels along the boundary between the two media. However, if the angle of incidence exceeds the critical angle, the light will undergo total internal reflection, meaning no light passes through, and all of it is reflected back into the original medium.

- The critical angle is the specific angle of incidence, measured with respect to the normal (a line perpendicular to the boundary), above which total internal reflection occurs.

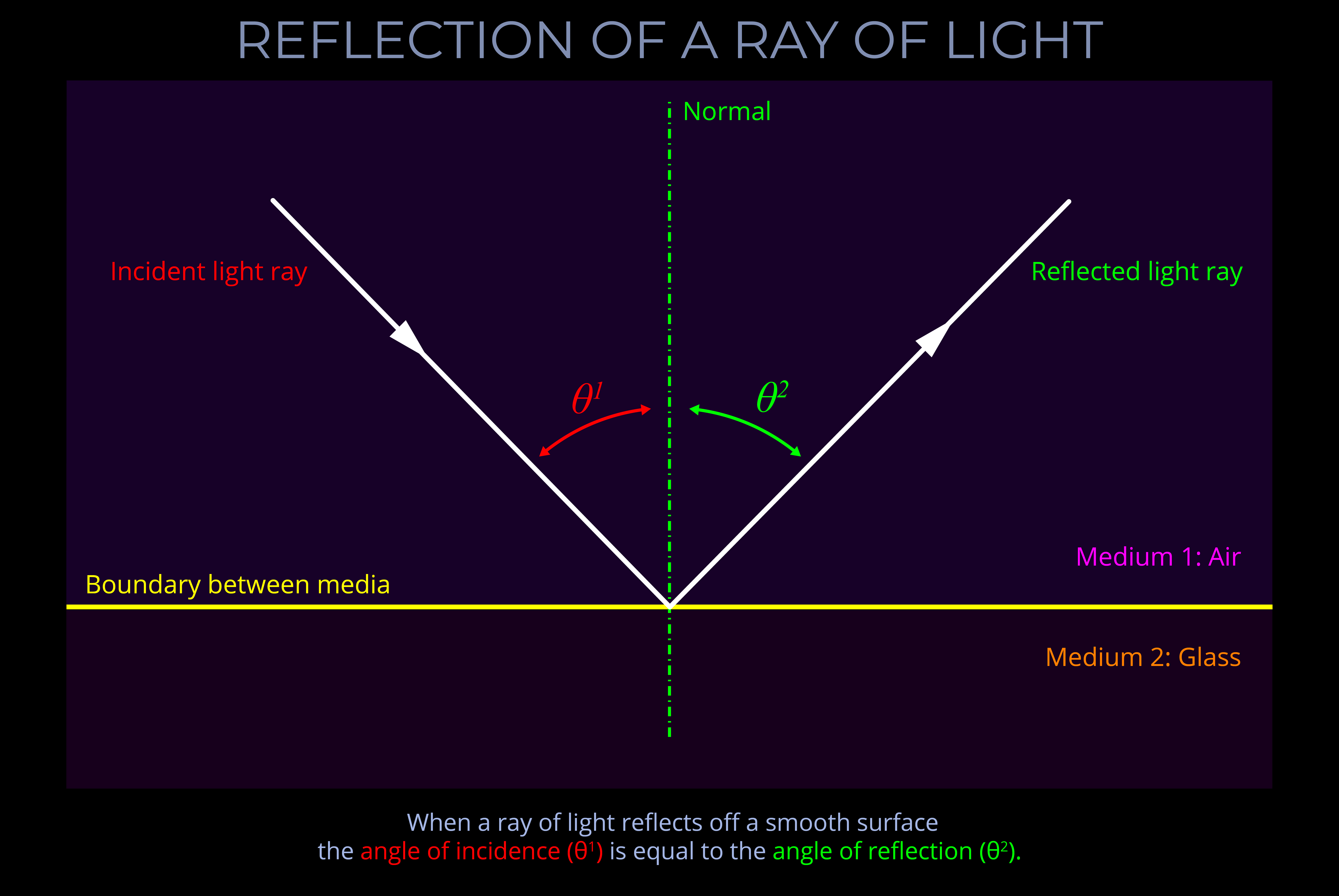

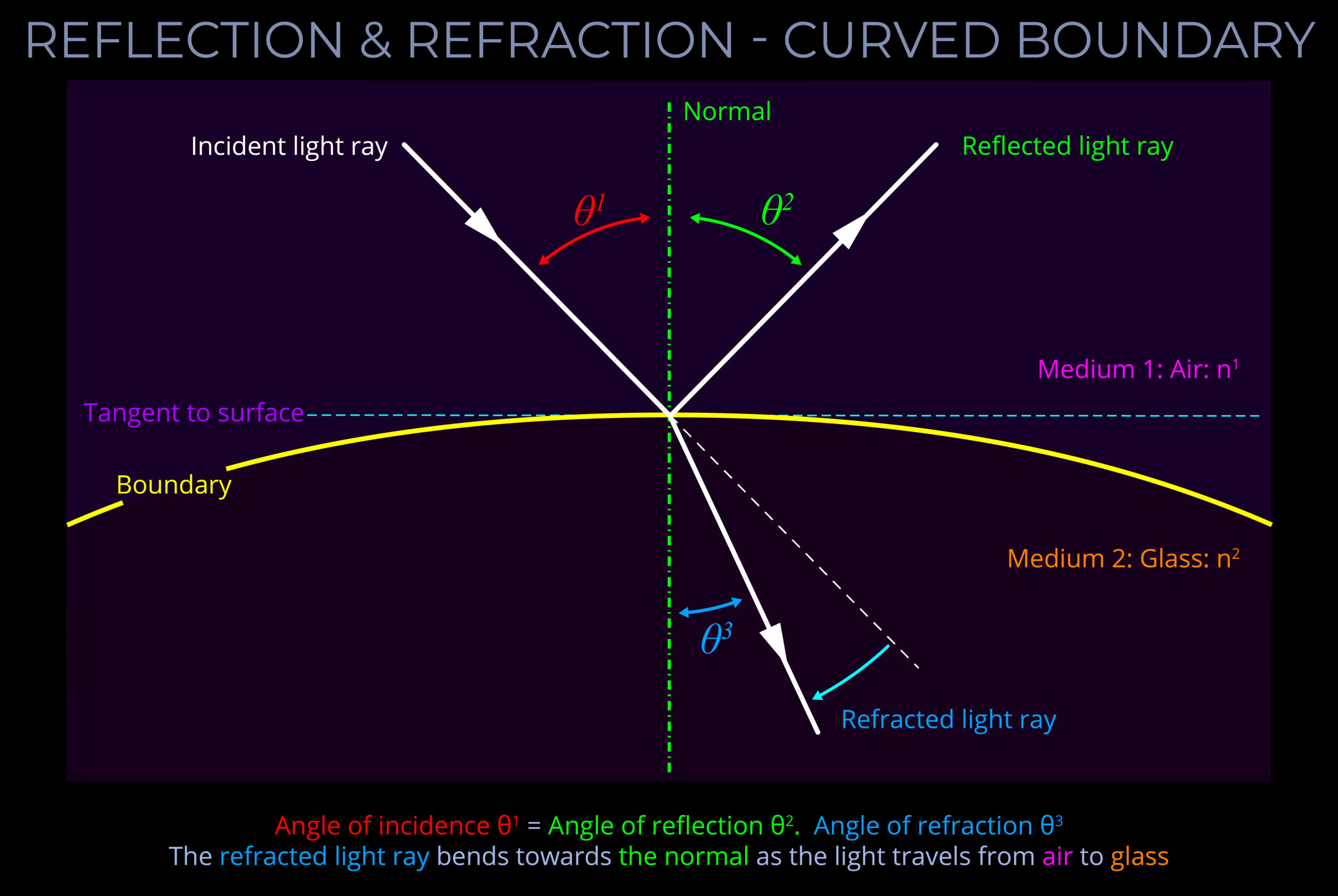

- In ray diagrams, the normal is an imaginary line drawn perpendicular to the boundary between two media, and the angle of refraction is measured between the refracted ray and the normal. If the boundary is curved, the normal is drawn perpendicular to the curve at the point of incidence.

Interneurons are a type of neuron found in the nervous system of animals, including humans, which play a role in processing and communicating information.

- Interneurons can be classified into different types based on their functions, such as local circuit interneurons and relay interneurons.

- Local circuit interneurons have short axons and form circuits with nearby neurons to analyse and process information locally.

- Relay interneurons have long axons and connect circuits of neurons in different regions of the central nervous system, enabling communication and integration of information.

- Interneurons can be further classified into sub-classes based on their neurotransmitter type, morphology, and connectivity.

- Interneurons serve as nodes within neural circuits, enabling communication and integration of sensory and motor information between the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system.

A typical atmospheric rainbow includes six bands of colour from red to violet but there are other bands of light present that don’t produce the experience of colour for human observers.

- It is useful to remember that:

- Each band of wavelengths within the electromagnetism spectrum (taken as a whole) is composed of photons that produce different kinds of light.

- Remember that light can be used to mean visible light but can also be used to refer to other areas of the electromagnetism spectrum invisible to the human eye.

- Each band of wavelengths represents a different form of radiant energy with distinct properties.

- The idea of bands of wavelengths is adopted for convenience sake and is a widely understood convention. The entire electromagnetic spectrum is, in practice, composed of a smooth and continuous range of wavelengths (frequencies, energies).

- Radio waves, at the end of the electromagnetic spectrum with the longest wavelengths and the least energy, can penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere and reach the ground but are invisible to human eyes.

- Microwaves have shorter wavelengths than radio waves, can penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere and reach the ground but are invisible to human eyes.

- Longer microwaves (waves with similar lengths to radio waves) pass through the Earth’s atmosphere more easily than the shorter wavelengths nearer the visible parts of spectrum.

- Infra-red is the band closest to visible light but has longer wavelengths. Infra-red radiation can penetrate Earth’s atmosphere but is absorbed by water and carbon dioxide. Infra-red light doesn’t register as a colour to the human eye.

- The human eye responds more strongly to some bands of visible light between red and violet than others.

- Ultra-violet light contains shorter wavelengths than visible light, can penetrate Earth’s atmosphere but is absorbed by ozone. Ultra-violet light doesn’t register as a colour to the human eye.

- Radio, microwaves, infra-red, ultra-violet are all types of non-ionizing radiation, meaning they don’t have enough energy to knock electrons off atoms. Some cause more damage to living cells than others.

- The Earth’s atmosphere is opaque to both X-rays or gamma-rays from the ionosphere downwards.

- X-rays and gamma-rays are both forms of ionising radiation. This means that they are able to remove electrons from atoms to create ions. Ionising radiation can damage living cells.

Remember that:

- All forms of electromagnetic radiation can be thought of in terms of waves and particles.

- All forms of light from radio waves to gamma-rays can be thought to propagate as streams of photons.

- The exact spread of colours seen in a rainbow depends on the complex of wavelengths emitted by the light source and which of those reach an observer.

The joule (J) is the unit of energy, work, and heat in the International System of Units (SI).

- One joule is equal to the amount of work done when a force of one newton displaces an object by one meter in the direction of that force.

- It can also be defined as the amount of energy dissipated as heat when an electric current of one ampere flows through a resistance of one ohm for one second.

- While joules are a fundamental unit, they are a relatively small unit of energy. Therefore, larger units like kilojoules (kJ) or megajoules (MJ) are often used for practical applications.