Rainbow Anatomy

£0.00

This is one of a set of almost 40 diagrams exploring Rainbows.

Each diagram appears on a separate page and is supported by a full explanation.

- Follow the links embedded in the text for definitions of all the key terms.

- For quick reference don’t miss the summaries of key terms further down each page.

Description

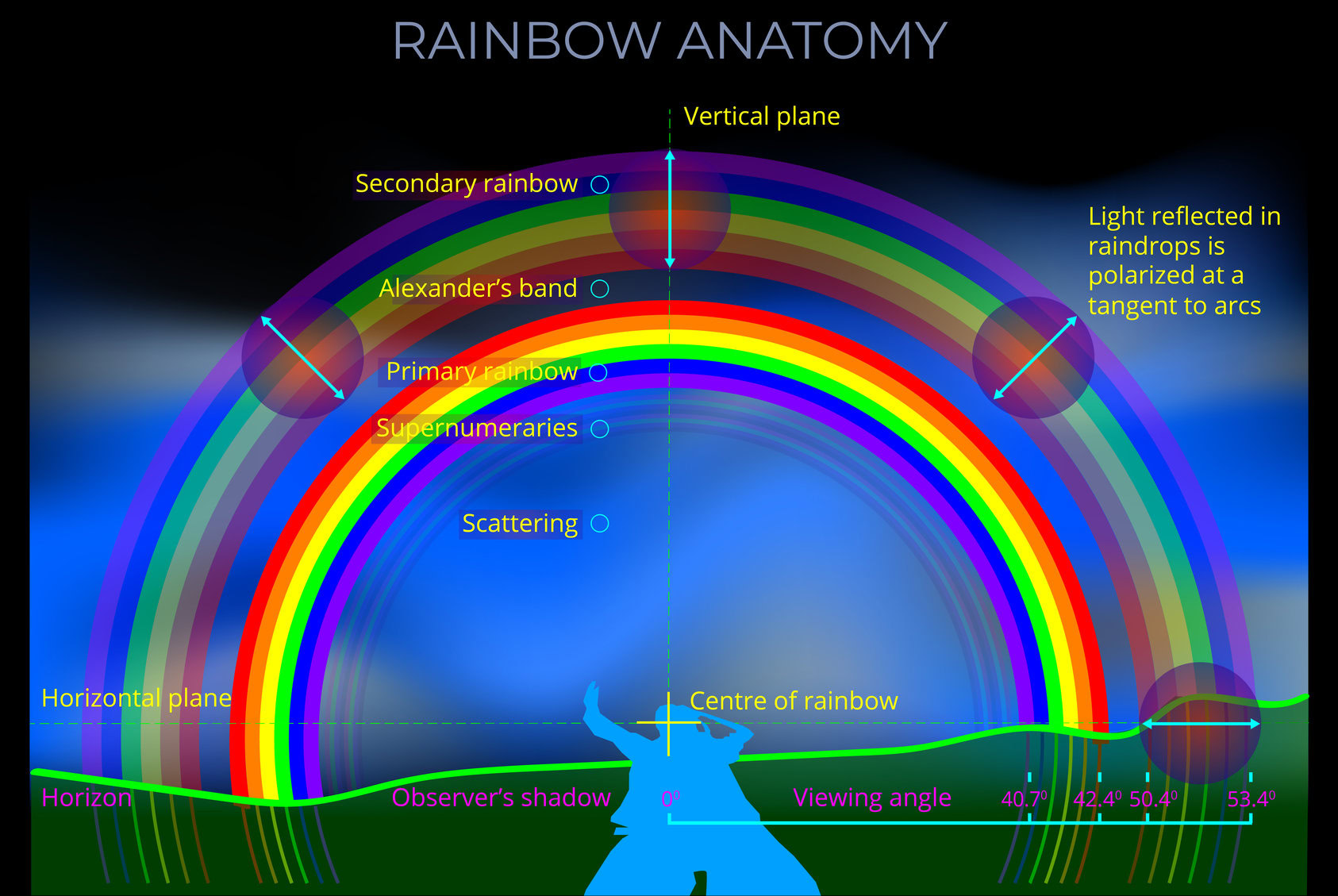

Rainbow Anatomy

TRY SOME QUICK QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS TO GET STARTED

About the Diagram

An overview of rainbows

About the diagram: Labels

This diagram includes labels that identify some key features of rainbows.

The two sections directly below this one help to build up an overview of rainbows. But if you want to find out more about each label on the diagram then go to Rainbows: In detail (further down the page) and look at the following headings:

- 5.1 Primary rainbow

- 5.2 Secondary rainbow

- 5.4 Alexander’s band

- 5.5 Supernumeraries

- 4.7 Scattering

- 2.6 Sun, observer and anti-solar point

- 6.7 Raindrops and polarization

- 7.3.b Angular distance

Looking closely at rainbows

An observer’s point of view

Some key terms

A human observer is a person who engages in observation by watching things.

- In the presence of visible light, an observer perceives colour because the retina at the back of the human eye is sensitive to wavelengths of light that fall within the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- The visual experience of colour is associated with words such as red, blue, yellow, etc.

- The retina’s response to visible light can be described in terms of wavelength, frequency and brightness.

- Other properties of the world around us must be inferred from light patterns.

- An observation can take many forms such as:

- Watching an ocean sunset or the sky at night.

- Studying a baby’s face.

- Exploring something that can’t be seen by collecting data from an instrument or machine.

- Experimenting in a laboratory setting.

- The observer effect is a principle of physics and states that any interaction between a particle and a measuring device will inevitably change the state of the particle. This is because the act of measurement itself imposes a disturbance on the particle’s wave function, which is the mathematical description of its state.

- The concept of observation refers to the act of engaging with an electron or other particle, achieved through measuring its position or momentum.

- In the context of quantum mechanics, observation isn’t a passive undertaking, observation actively alters a particle’s state.

- This means that any kind of interaction with an atom, or with one of its constituent particles, that provides insight into its state results in a change to that state. The act of observation is always intrusive and will always change the state of the object being observed.

- It can be challenging to reconcile this with our daily experience, where we believe we can observe things without inducing any change in them.

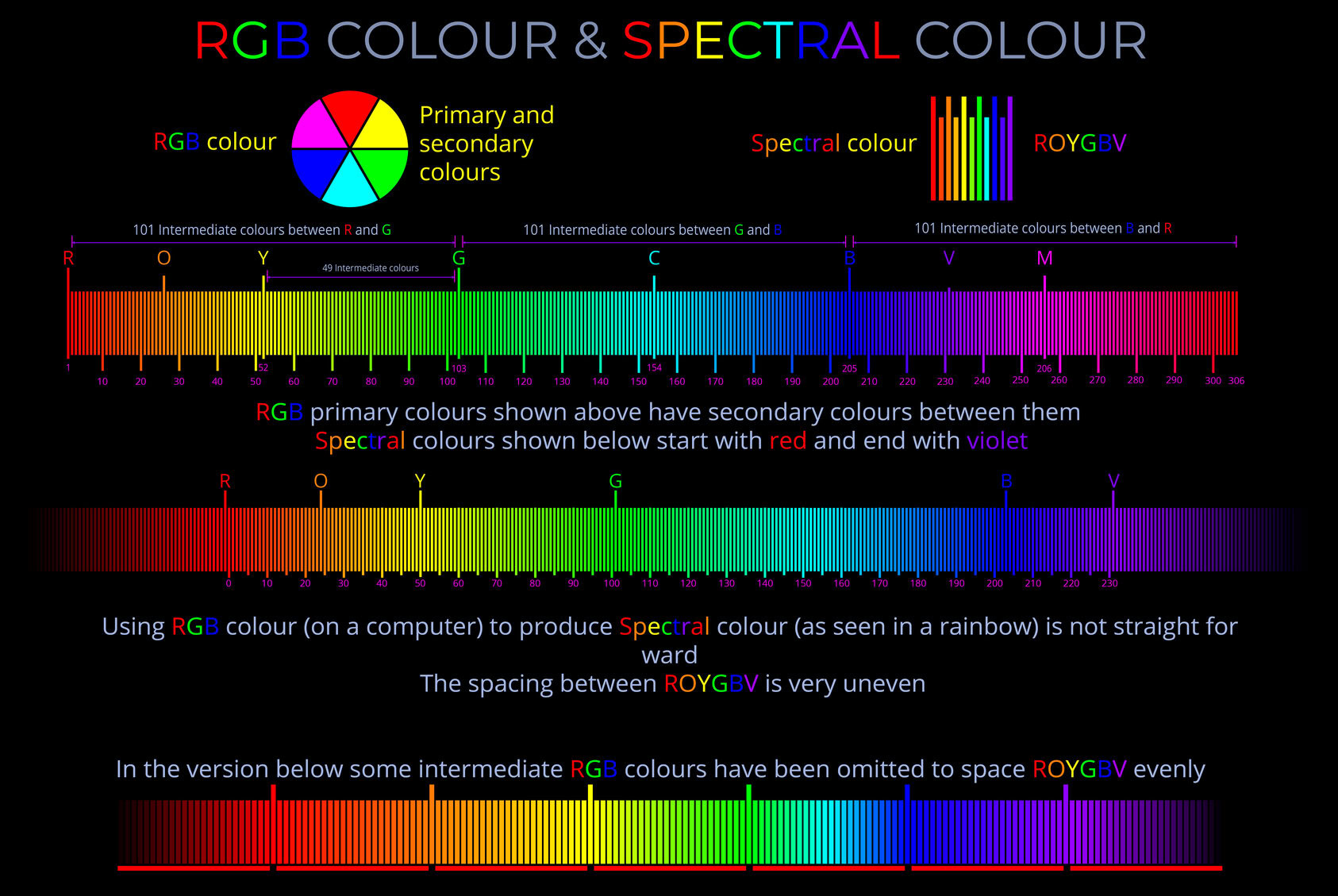

The spectral colour model represents the range of pure colours that correspond to specific wavelengths of visible light. These colours are called spectral colours because they are not created by mixing other colours but are produced by a single wavelength of light. This model is important because it directly reflects how human vision perceives light that comes from natural sources, like sunlight, which contains a range of wavelengths.

- The spectral colour model is typically represented as a continuous strip, with red at one end (longest wavelength) and violet at the other (shortest wavelength).

- Wavelengths and Colour Perception: In the spectral colour model, each wavelength corresponds to a distinct colour, ranging from red (with the longest wavelength, around 700 nanometres) to violet (with the shortest wavelength, around 400 nanometres). The human eye perceives these colours as pure because they are not the result of mixing other wavelengths.

- Pure Colours: Spectral colours are considered “pure” because they are made up of only one wavelength. This is in contrast to colours produced by mixing light (like in the RGB colour model) or pigments (in the CMY model), where a combination of wavelengths leads to different colours.

- Applications: The spectral colour model is useful in understanding natural light phenomena like rainbows, where each visible colour represents a different part of the light spectrum. It is also applied in fields like optics to describe how the eye responds to light in a precise, measurable way.

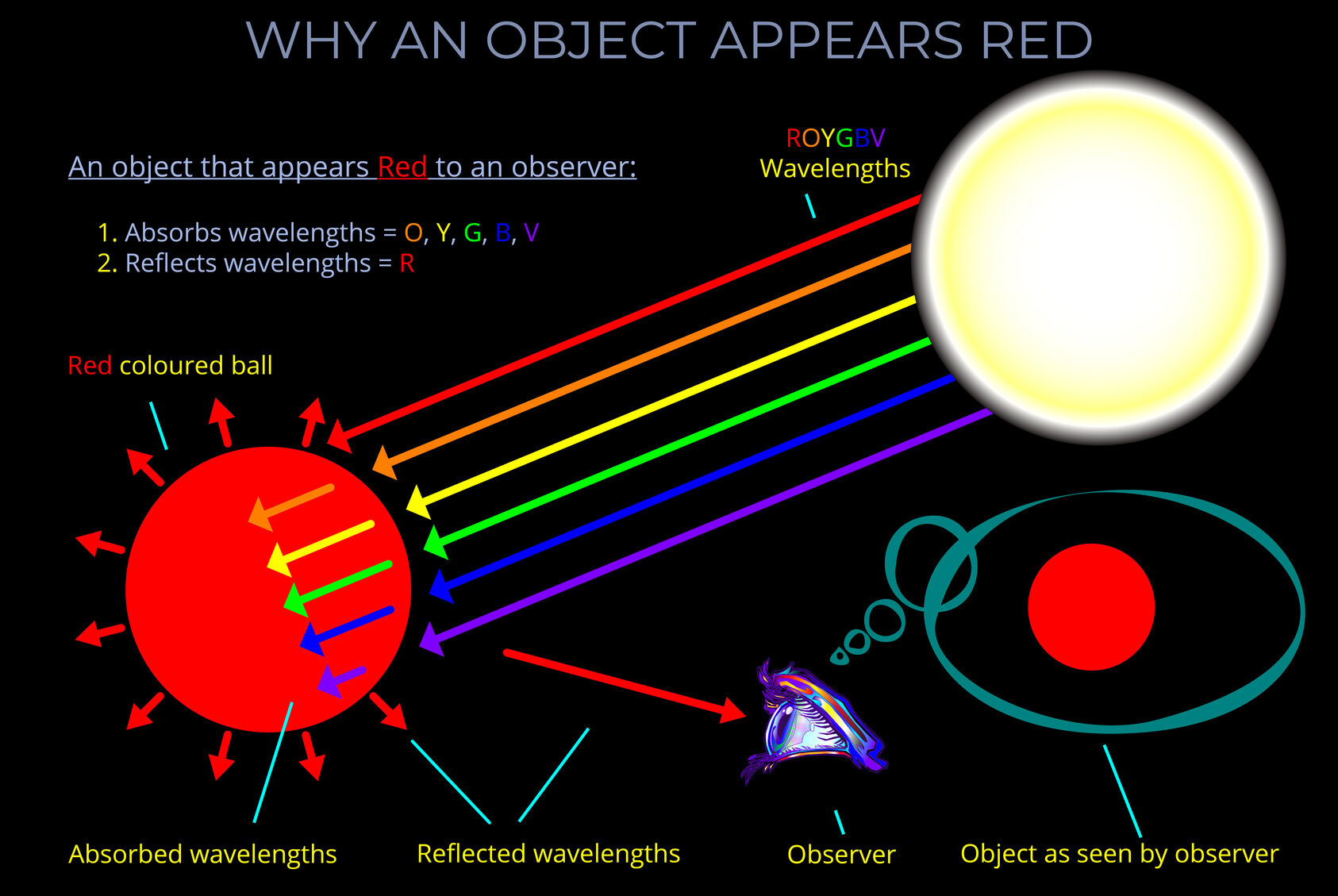

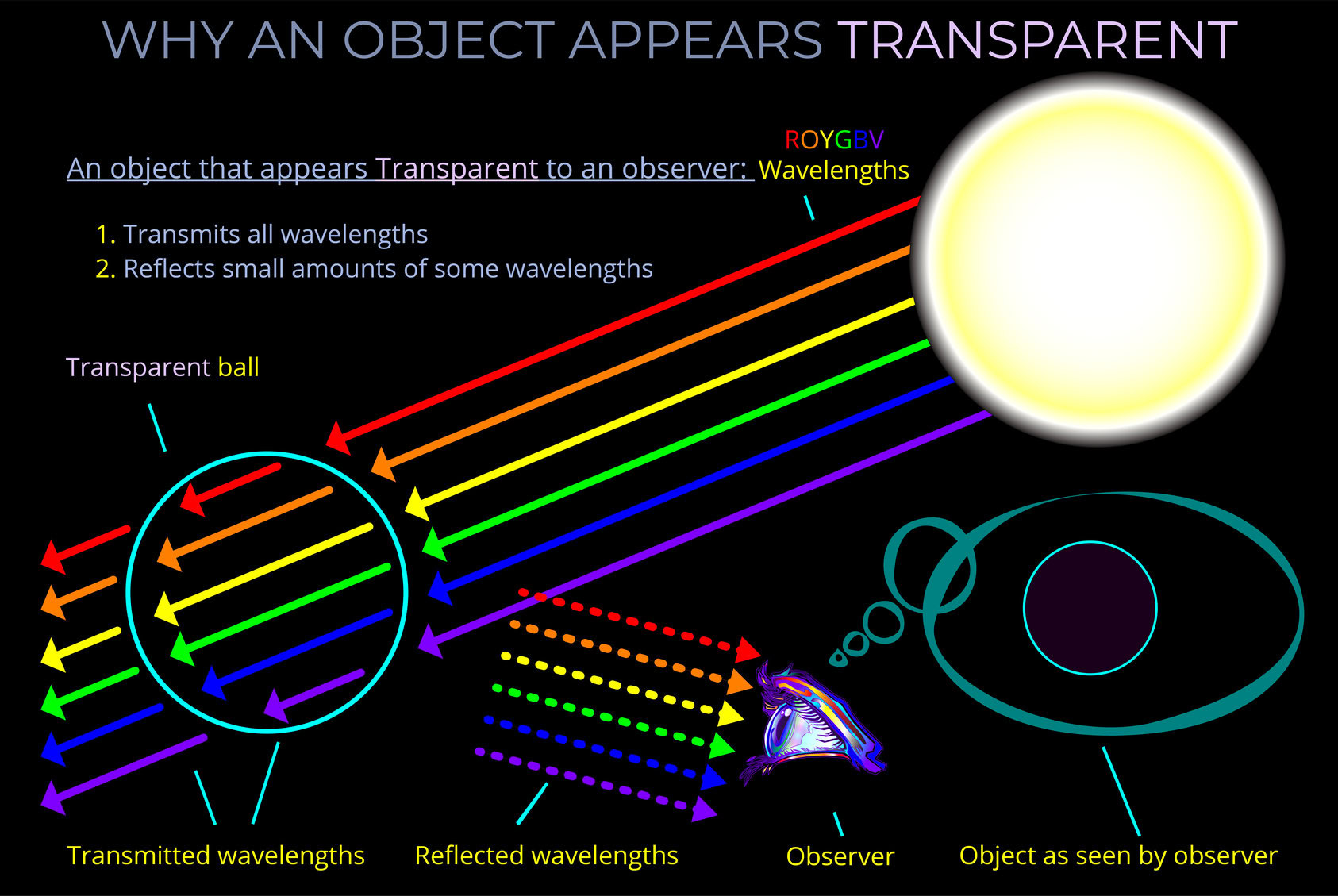

Reflection is the process where light rebounds from a surface into the medium it came from, instead of being absorbed by an opaque material or transmitted through a transparent one.

- The three laws of reflection are as follows:

- When light hits a reflective surface, the incoming light, the reflected light, and an imaginary line perpendicular to the surface (called the “normal line”) are all in the same flat area.

- The angle between the incoming light and the normal line is the same as the angle between the reflected light and the normal line. In other words, light bounces off the surface at the same angle as it came in.

- The incoming and reflected light are mirror images of each other when looking along the normal line. If you were to fold the flat area along the normal line, the incoming light would line up with the reflected light.

Sunlight, also known as daylight or visible light, refers to the portion of electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun that is detectable by the human eye. It is one form of the broad range of electromagnetic radiation produced by the Sun. Our eyes are particularly sensitive to this specific range of wavelengths, enabling us to perceive the Sun and the world around us.

- Sunlight is only one form of electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun.

- Sunlight is only a very small part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Sunlight is the form of electromagnetic radiation that our eyes are sensitive to.

- Other types of electromagnetic radiation that we are sensitive to, but cannot see, are infrared radiation that we feel as heat and ultraviolet radiation that causes sunburn.

In the field of optics, dispersion is shorthand for chromatic dispersion which refers to the way that light, under certain conditions, separates into its component wavelengths, enabling the colours corresponding with each wavelength to become visible to a human observer.

- Chromatic dispersion refers to the dispersion of light according to its wavelength or colour.

- Chromatic dispersion is the result of the relationship between wavelength and refractive index.

- When light travels from one medium (such as air) to another (such as glass or water) each wavelength is refracted differently, causing the separation of white light into its constituent colours.

- When light undergoes refraction each wavelength changes direction by a different amount. In the case of white light, the separate wavelengths fan out into distinct bands of colour with red on one side and violet on the other.

- Familiar examples of chromatic dispersion are when white light strikes a prism or raindrops and a rainbow of colours becomes visible to an observer.

Refraction refers to the way that electromagnetic radiation (light) changes speed and direction as it travels across the boundary between one transparent medium and another.

- Light bends towards the normal and slows down when it moves from a fast medium (like air) to a slower medium (like water).

- Light bends away from the normal and speeds up when it moves from a slow medium (like diamond) to a faster medium (like glass).

- These phenomena are governed by Snell’s law, which describes the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction.

- The refractive index (index of refraction) of a medium indicates how much the speed and direction of light are altered when travelling in or out of a medium.

- It is calculated by dividing the speed of light in a vacuum by the speed of light in the material.

- Snell’s law relates the angles of incidence and refraction to the refractive indices of the two media involved.

- Snell’s law states that the ratio of the sine of the angle of incidence to the sine of the angle of refraction is equal to the ratio of the refractive indices.