Experience of seeing

Colour is something we see every moment of our lives if we are conscious and exposed to light. Some people have limited colour vision and so rely more heavily on other senses – touch, hearing, taste and smell.

Colour is always there whether we are aware and pay attention to it or not. Colour is what human beings experience in the presence of light. It is important to be clear about this. Unless light strikes something, whether it is air, a substance like water, a physical object or the retina at the back of our eyes, light, as it travels through space, is invisible and so has no colour whatsoever. colour is an artefact of human vision, something that only exists for living things like ourselves. Seeing is a sensation that allows us to be aware of light and takes the form of colour.

The experience of colour is unmediated. This means that it is simply what we see and how the world appears. In normal circumstances, we feel little or nothing of what is going on as light enters our eyes. We have no awareness whatsoever of the chemical processes going on within photosensitive neurons or of electrical signals beginning their journey towards the brain. We know nothing of what goes on within our visual cortex when we register a yellow ball or a red house. The reality is, we rarely even notice when the world disappears as we blink! In terms of immediate present perception, colour is simply something that is here and now, it is that aspect of the world we see as life unfolds before us and is augmented by our other senses, as well as by words, thoughts and feelings etc.

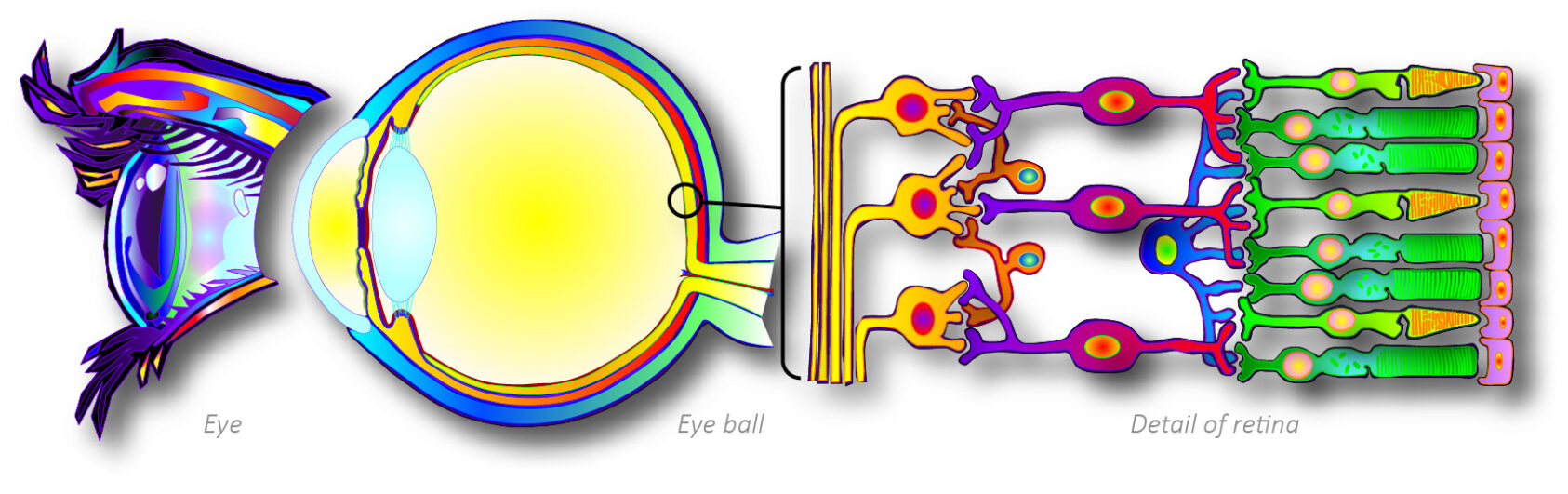

It takes about 0.15 seconds from the moment light enters the human eye to conscious recognition of basic objects. What happens during this time is related to the visual pathway that can be traced from the inner surface of the eyeball to the brain and then into our conscious experience. The route is formed from cellular tissue including chains of neurons some of which are photosensitive, with others tuned to fulfil related functions.

So, let’s start at the beginning!

Before light enters the eye and stimulates the visual system of a human observer it is often reflected off the surfaces of objects within our field of view. When this happens, unless the surface is mirror-like, it scatters in all directions and only a small proportion travels directly towards our eyes. Some of the scattered light may illuminate the body or face of an observer or miss them completely. Some is reflected back off the iris enabling others to see the colour of their eyes. Sometimes light is also reflected off the inside of our eyeballs – think of red-eye in flash photography.

Cross-section of the human eyeball

Cross-section of the human eyeball

The fraction of light that really counts passes straight through the pupil and lens and strikes the retina at the back of the eyeball. From the point of view of an observer, this leads to two experiences:

- Things an observer sees right in the centre of their field of vision, which is to say, whatever they are looking at.

- Things an observer sees in their peripheral vision and so fill the remainder of a scene.

If we think of light in terms of rays, then the centre of the field of vision is formed from rays that enter our eyes perpendicular to the curvature of the cornea, pass right through the centre of the pupil and lens and then continue in a straight line through the vitreous humour until they strike the retina. Because these rays are perfectly aligned with our eyeballs they do not bend as they pass through the lens and so form an axis around which everything else is arranged. The point where this axis strikes the retina is called the macula and at its centre is the fovea centralis where the resulting image appears at its sharpest.

Peripheral vision is formed from rays that are not directly aligned with the central axis of the cornea and pupil, and do not pass through the very centre of the lens. All the rays of light around this central axis of vision change direction slightly because of refraction.

It deserves mention at this point that the lenses in each eye focus in unison to accommodate the fact those things we scrutinise most carefully may be anywhere from right in front of our noses to distant horizons.

We must also not forget that the optical properties of our lenses mean that the image that forms on the retina is both upside down and the wrong way round.