THE EXPERIENCE OF COLOUR

Colour is something we see every moment of our lives if we are conscious and exposed to light. Some people have limited colour vision and so rely more heavily on other senses – touch, hearing, taste and smell.

Colour is always there whether we are aware and pay attention to it or not. Colour is what human beings experience in the presence of light. It is important to be clear about this. Unless light strikes something, whether it is air, a substance like water, a physical object or the retina at the back of our eyes, light, as it travels through space, is invisible and so has no colour whatsoever. As suggested in the previous section, colour is an artefact of human vision, something that only exists for living things like ourselves. Seeing is a sensation that makes us aware of light and takes the form of colour.

The experience of colour is unmediated. This means that it is simply what we see and how the world appears. In normal circumstances, we feel little or nothing of what is going on as light enters our eyes. We have no awareness whatsoever of the chemical processes going on within photosensitive neurons or of electrical signals on their way to the brain. We know nothing of what goes on within our visual cortex when we register a yellow ball or a red house. The reality is, we rarely even notice when we blink! In terms of immediate present perception, colour is simply something that is here and now, it is an aspect of the world we see as life unfolds before us and is augmented by our other senses, as well as by words, thoughts and feelings etc.

It takes about 0.15 seconds from the moment light enters the human eye to conscious recognition of basic objects. What happens during this time is related to the visual pathway that can be traced from the inner surface of the eyeball to the brain and then into conscious experience. The route is formed from cellular tissue including chains of neurons some of which are photosensitive, with others tuned to fulfil related functions.

So, let’s start at the beginning!

Before light enters the eye and stimulates the visual system of a human observer it is often reflected off the surfaces of objects within the field of view. When this happens, unless the surface is mirror-like, it scatters in all directions and so only a small proportion travels directly towards the eyes. Some of the scattered light may illuminate the body or face of the observer or miss them completely. Some is reflected off the iris and enables us to see the colour of a person’s eyes. A little more is reflected off the retina – think of red-eye in flash photography.

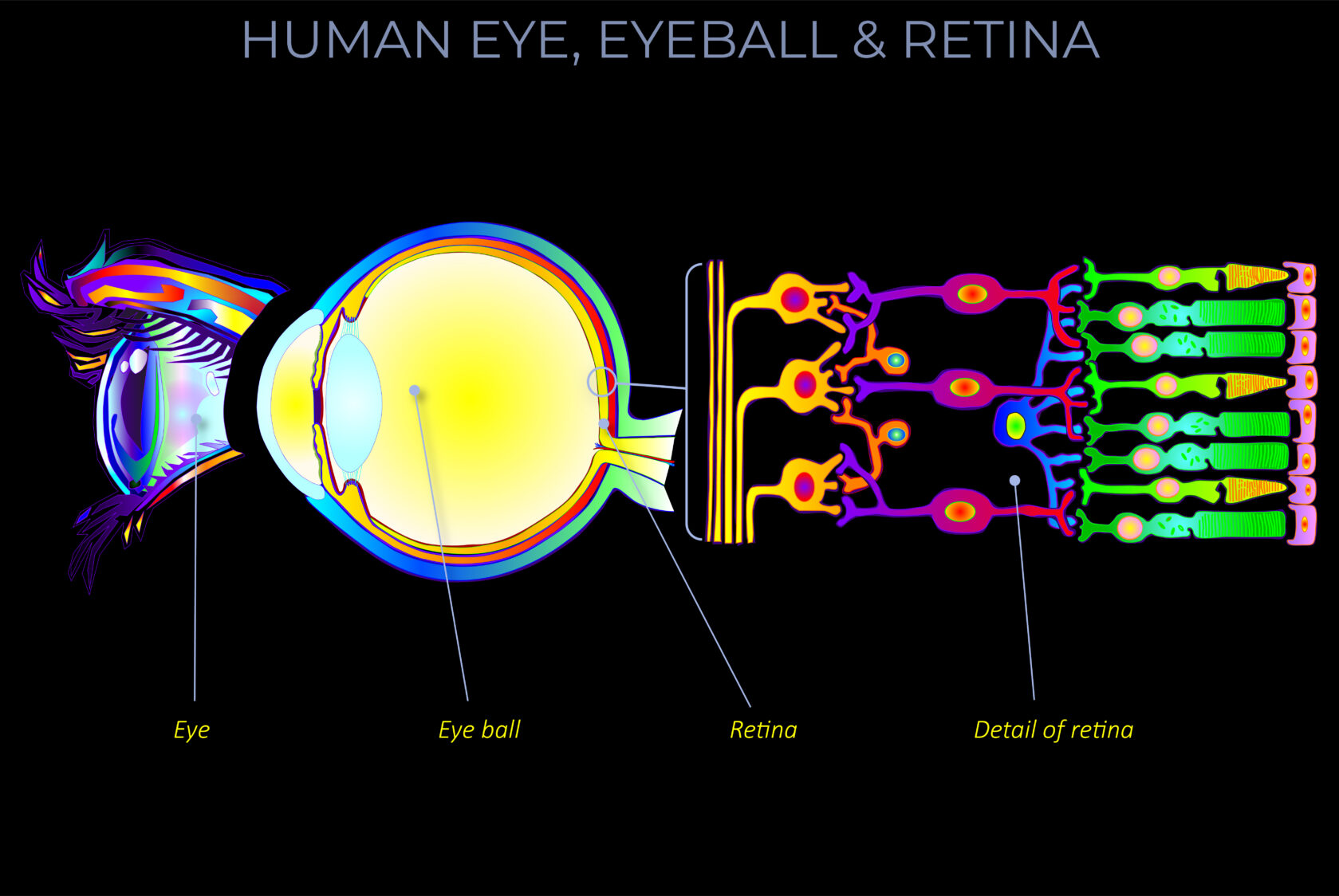

Cross-section of the human eyeball

If we think of light in terms of rays, then some rays will be in line with the eyes of our observer as they look at an object. Rays that strike the outer surface of the eyeball directly in front of the pupil encounter various transparent media including the cornea, then the lens followed by vitreous humour, the gel that fills the eyeball. Then, they arrive at the retina.

Along an axis corresponding with the central line of vision, light enters perpendicular to the curvature of the cornea and travels straight towards the retina striking the fovea centralis at the centre of the macula where the sharpest image is formed. All the rays of light around this central line of vision change direction slightly because of refraction. The lens also affects their direction of travel as it adjusts in shape to ensure that as many rays as possible are focused exactly onto the retinal surface.

THE RETINA

Human beings see the world in colour because of the way their visual system processes light. The retina contains light-sensitive receptors, rod and cone cells, that respond to light stimuli. It is the variety of wavelengths and intensities of light entering the eyes that produces the impression of colour.

The retina is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue inside our eyes. It forms a sheet of tissue barely 200 micrometres (μm) thick, but its neural networks carry out almost unimaginably complicated feats of image processing.

The physiology of the eye results in a tiny, focused, two-dimensional image of the visual world being projected onto the retina’s surface. Because of the optics of lenses, it appears upside down and the wrong way around. But no worry, sorting that out is child’s play for the human brain! The real challenge is that the photosensitive receptors in the retina must produce precise chemical responses to light and translate every minute detail of the image into electrical impulse ready to be sent to the brain where they produce visual impressions of the world. In a very limited sense, the retina serves a similar function to a photosensitive chip in a camera.

As research continues to reveal ever-increasing amounts of detail about these signalling processes across and beyond the retina, it required new thinking, not only of the retina’s function but also of the mechanisms within the brain that shape these signals into behaviourally useful perceptions.

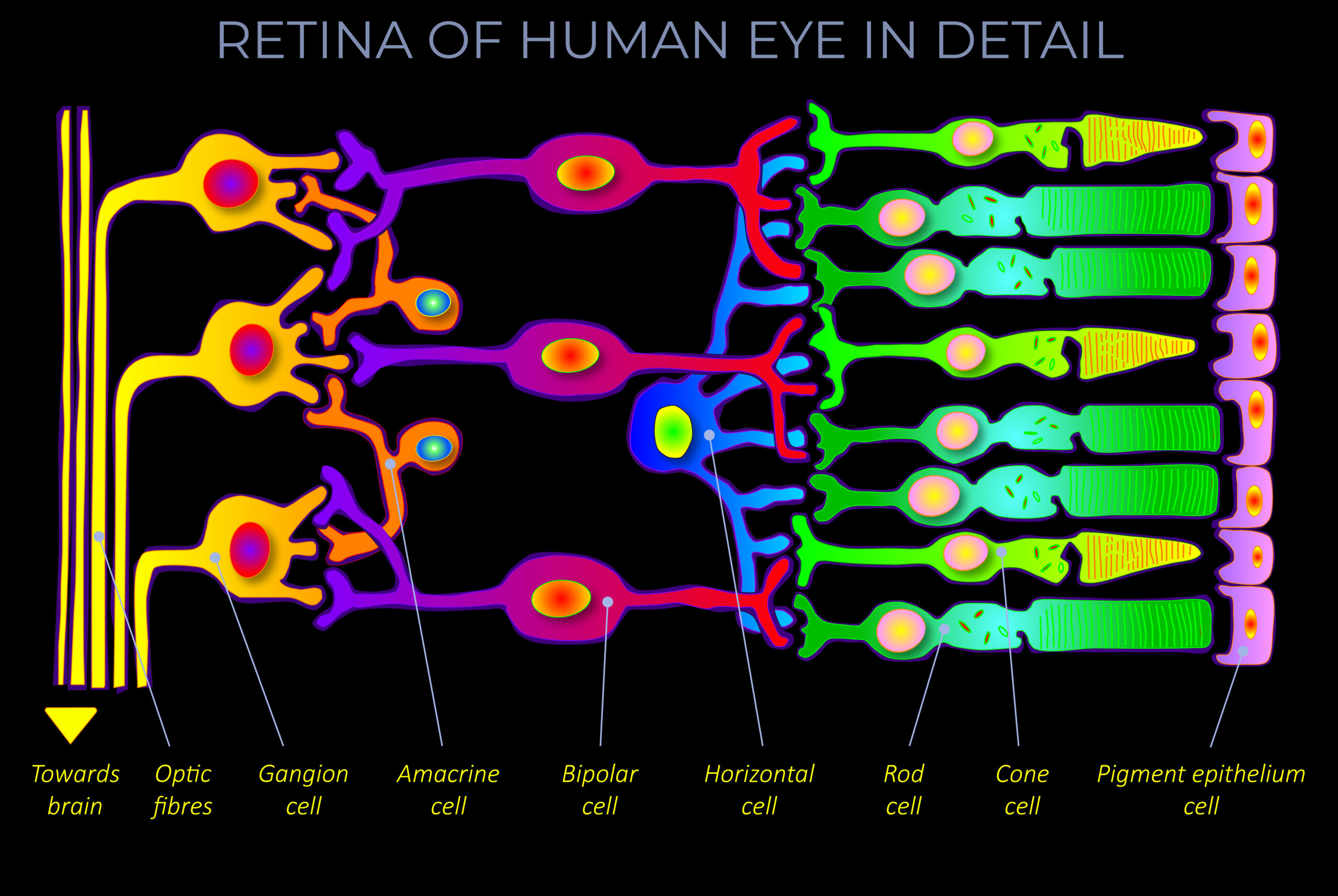

The retina consists of 60-plus distinct neuron-types, each of which plays a specialized role in turning variations in the patterns of wavelengths and intensities of light into visual information. Neurons are electrically excitable nerve cells that collect, process and transmit vast amounts of this information through both chemical and electrical signals. Retinal neurons work together to convert the signals produced by a hundred and twenty million rods and cones and send them along around one million fibres within the optic nerve of each eye to connections with higher brain functions. In this process rods and cones are first responders whilst ganglion cells are the final port of call before information leaves the retina.

There are three principal forms of processing that take place within the retina itself. The first organises the outputs of the rod and cone photoreceptors and begins to compose them into around 12 parallel information streams as they travel through bipolar cells. The second connects these streams to specific types of retinal ganglion cells. The third modulates the information using feedback from horizontal and amacrine cells to create the diverse encodings of the visual world that the retina transmits towards the brain.

As mentioned above, the image of the outside world focused on the retina is upside down and the wrong way around. But the human retina is also inverted in the sense that the light-sensitive rod and cone cells are not located on the surface where the image forms, but instead are embedded inside, where the retina attaches to the fabric of the eyeball. As a result, light striking the retina, passes through layers of other neurons (ganglion, bipolar cells etc.) and blood-carrying capillaries, before reaching the photoreceptors.

The overlying neural fibres do not significantly degrade vision in the inverted retina. The neurons are relatively transparent and accompanying Müller cells act as fibre-optic channels to transport photons directly to photoreceptors. However, some estimates suggest that overall, around 15% of all the light entering the eye is lost en-route to the retina. To counter this, the fovea centralis, at the centre of our field of vision, is free of rods and there are no blood vessels running through it, so optimising the level of detail where we need it most.

Human eye, eyeball and retina

Human eye, eyeball and retina

From retinal input to cortical processing and perception

Visual input is initially encoded in the retina as a two-dimensional distribution of light intensity, expressed as a function of position, wavelength and time in each of the two eyes. This retinal image is transferred to the visual cortex where primary sensory cues and, later, inferred attributes, are eventually computed (see figure). Parallel processing strategies are employed from the outset to overcome the constraints of the individual ganglion cell’s limited bandwidth and the anatomical bottleneck of the optic nerve.

Retina of the Human Eye in Detail

Retina of the Human Eye in Detail

Rods and cones

Both the photosensitive rods and cones form a regularly spaced mosaic of cells across the entirety of the retina – bar the absence of rods in the fovea centralis. Because there are 100 million rod receptors and 20 million cone receptors in each eye, rods are packed more densely per unit area. The synaptic connections of both rods and cones vary in function in different locations across the retina, reflecting the specialisations of different regions. This, for example, allows the eyes to deal with daylight and darkness and with what we see at the centre and periphery of our field of view.

Rods and cones are easily distinguished by their shape, from which they derive their names, the type of photopigment they contain and by distinct patterns of synaptic connections with the other neurons around them.

Neurons (nerve cells) are present throughout the human central and peripheral nervous systems and fall into three main categories: sensory, motor and interneurons. Rods and cones are both sensory neurons. Rods don’t produce as sharp an image as cone cells because they share more connections with other types of neurons. But a rod cell is believed to be sensitive enough to respond to a single photon of light whilst cone cells require tens to hundreds of photons to be activated.

The principal task of rod and cone cells alike is phototransduction. This refers to the type of sensory transduction that takes place in the visual system. It is the process of phototransduction that enables pigmented chemicals in the rods and cones to sense light and convert it into electrical signals. Many other types of sensory transduction occur elsewhere within the body enabling touch and hearing for example.

Caption

Caption

Functional Specialization of the Rod and Cone Systems

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10850/

Trichromatic colour vision (Trichromacy)

Photo-transduction by cone cell receptors is the physiological basis for trichromatic colour vision in humans. The fact that we see colour is, in the first instance, the result of interactions among the three types of cones, each of which responds with a bias towards its favoured wavelength within the visible spectrum. The result is that the L, M and S cone types respond best to light with long wavelengths (biased towards 560 nm), medium wavelengths (biased towards 530 nm), and short wavelengths (biased towards 420 nm) respectively.

Caption

Caption

Trivariance

The term trivariance is used to refer to this first stage of the trichromatic process. It refers to both the phototransductive response of the cone cells themselves and to the three separate channels used to convey their colour information forward to subsequent levels of neural processing.

Each channel conveys information about the response of one cone-type to both the wavelength of the incoming light it is tuned to and to its intensity. In both physiological and neurological terms this process is exclusively concerned with trivariance – three discernible differences in the overall composition of light entering the eye.

It is the separation of the signals produced on each channel that accounts for the ability of our eyes to respond to stimuli produced by additive mixtures of wavelengths corresponding with red, green and blue primary colours. But more of that later!

By way of summary, the rod and trivariant cone systems are composed of photoreceptors with connections to other cell types within the retina. Both specialize in different aspects of vision. The rod system is extremely sensitive to light but has a low spatial resolution. Conversely, the cone system is designed to function in stronger light. As a result, cones are relatively insensitive compared with rods but have a very high spatial resolution. It is this specialisation that results in the extraordinary detail, resolution and clarity of human vision.

| Rod System | Cone System |

| High sensitivity, specialized for night vision | Lower sensitivity specialized for day vision |

| Saturate in daylight | Saturate only in intense light |

| Achromatic | Chromatic, mediate colour vision |

| Low acuity | High acuity |

| Not present in the central fovea | Concentrated in the central fovea |

| Present in larger number than cones | Present in smaller number than rods |

Caption

Retinal image

It is the cornea-lens system that determines where light falls on the surface of the retina which results in discernible images.

The images are inverted and obviously very small compared with the world outside that they resolve. The inversion poses no problem. Our brains are very flexible and even when tricked by prisms will always turn the world right-side-up given time. The reduction in size is part of the process by which the fit of the image on the retina determines our field of view.

The images are real in the sense that they are formed by the actual convergence of light rays onto the curved plane of the retina. Only real images of this kind provide the necessary stimulation of rod and cone cells necessary for human perception.

Caption

Caption

Fovea centralis

The entire surface of the retina contains nerve cells, but there is a small portion with a diameter of approximately 0.25 mm at the centre of the macula called the fovea centralis where the concentration of cones is greatest. This region is the optimal location for the formation of image detail. The eyes constantly rotate in their sockets to focus images of objects of interest as precisely as possible at this location.

Caption

Caption

Accommodation

The distance between the retina (the detector) and the cornea (the refractor) is fixed in the human eyeball. The eye must be able to alter the focal length of the lens in order to accurately focus images of both nearby and far away objects on the retinal surface. This is achieved by small muscles that alter the shape of the lens. The distance of objects of interest to an observer varies from infinity to next to nothing but the image distance remains constant.

The ability of the eye to adjust its focal length is known as accommodation. The eye accommodates by assuming a lens shape that has a shorter focal length for nearby objects in which case the ciliary muscles squeeze the lens into a more convex shape. For distant objects, the ciliary muscles relax, and the lens adopts a flatter form with a longer focal length.

Caption

Caption

Bipolar cells

Bipolar cells, a type of neuron found in the retina of the human eye connect with other types of nerve cells via synapses. They act, directly or indirectly, as conduits through which to transmit signals from photoreceptors (rods and cones) to ganglion cells.

There are around 12 types of bipolar cells and each one functions as an integrating centre for a different parsing of information extracted from the photoreceptors. So, each type transmits a different analysis and interpretation of the information it has gathered.

The output of bipolar cells onto ganglion cells includes both the direct response of the bipolar cell to signals derived from photo-transduction but also responses to those signals received indirectly from information provided by nearby amacrine cells that are also wired into the circuitry.

We might imagine one type of bipolar cell connecting directly from a cone to a ganglion cell that simply compares signals based on differences in wavelength. The ganglion cell might then use the information to determine whether a certain point is a scene is red or green.

Not all bipolar cells synapse directly with a single ganglion cell. Some channel information that is sampled by different sets of ganglion cells. Others terminate elsewhere within the complex lattices of interconnections within the retina so enabling them to carry packets of information to an array of different locations and cell types.

Caption

Caption

Amacrine cells

Amacrine cells interact with bipolar cells and/or ganglion cells. They are a type of interneuron that monitor and augment the stream of data through bipolar cells and also control and refine the response of ganglion cells and their subtypes.

Amacrine cells are in a central but inaccessible region of the retinal circuitry. Most are without tale-like axons. Whilst they clearly have multiple connections to other neurons around them, their precise inputs and outputs are difficult to trace. They are driven by and send feedback to the bipolar cells but also synapse on ganglion cells, and with each other.

Amacrine cells are known to serve narrowly task-specific visual functions including:

- Efficient transmission of high-fidelity visual information with a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Maintaining the circadian rhythm, so keeping our lives tuned to the cycles of day and night and helping to govern our lives throughout the year.

- Measuring the difference between the response of specific photoreceptors compared with surrounding cells (centre-surround antagonism) which enables edge detection and contrast enhancement.

- Object motion detection which provides an ability to distinguish between the true motion of an object across the field of view and the motion of our eyes.

Centre-surround antagonism refers to the way retinal neurons organize their receptive fields. The centre component is primed to measure the sum-total of signals received from a small number of cones directly connected to a bipolar cell. The surround component is primed to measure the sum of signals received from a much larger number of cones around the centre point. The two signals are then compared to find the degree to which they agree or disagree.

Caption

Caption

Horizontal cells

Horizontal cells are connected to rod and cone cells by synapses and are classed as laterally interconnecting neurons.

Horizontal cells help to integrate and regulate information received from photoreceptor cells, cleaning up and globally adjusting signals passing through bipolar cells towards the regions containing ganglion cells.

An important function of horizontal cells is enabling the eye to adjust to both bright and dim light conditions. They achieve this by providing feedback to rod and cone photoreceptors about the average level of illumination falling onto specific regions of the retina.

If a scene contains objects that are much brighter than others, then horizontal cells are believed to prevent signals representing the brightest objects from dazzling the retina and degrading the overall quality of information.

Caption

The Neuronal Organization of the Retina Richard H. Masland

https://www.cell.com/neuron/fulltext/S0896-6273(12)00883-5?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0896627312008835%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

Ganglion cells

Retinal ganglion cells are located near the boundary between the retina and the central chamber containing vitreous humour. They collect and process all the visual information gathered directly or indirectly from the forty-something types of rod, cone, bipolar, horizontal and amacrine cells and, once finished, transmit it via their axons towards higher visual centres within the brain.

The axons of ganglion cells form into the fibres of the optic nerve that synapse at the other end on the lateral geniculate nucleus. Axons take the form of long slender fibre-like projections of the cell body and typically conduct electrical impulses, often called action potentials, away from a neuron.

A single ganglion cell communicates with as few as five photoreceptors in the fovea at the centre of the macula. This produces images containing the maximum possible resolution of detail. At the extreme periphery of the retina, a single ganglion cell receives information from many thousands of photoreceptors.

Around twenty distinguishable functional types of ganglion cells resolve the information received from 120 million rods and cones into one million parallel streams of information about the world surveyed by a human observer in real-time throughout every day of their lives. They function to complete the construction of the foundations of visual experience by the retina, ordering the eyes response to light into the fundamental building blocks of vision. Ganglion cells do the groundwork that enables retinal encodings to ultimately converge into a unified representation of the visual world.

Ganglion cells not only deal with colour information streaming in from rod and cone cells but also with the deductions, inferences, anticipatory functions and modifications suggested by bipolar, amacrine and horizontal cells. Their challenge, therefore, is to enable all this data to converge and to assemble it into high fidelity, redundancy-free, compressed and coded form that can continue to be handled within the available bandwidth and so the data-carrying capacity of the optic nerve.

It is not hard to imagine the kind of challenges they must deal with:

- Information must feed into and support the distinct attributes of visual perception and be available to be resolved within the composition of our immediately present visual impressions whenever needed.

- Information must correspond with the outstanding discriminatory capacities that enable the visual system to operate a palette that can include millions of perceivable variations in colour.

- Information about the outside world must be able to be automatically cross-referenced, highly detailed, specifically relevant, spatial and temporally sequenced and available on demand.

- Information must be subjectively orientated in a way that it is locked at an impeccable level of accurate detail to even our most insane intentions as we leap from rock to rock across a swollen river or dive from an aircraft wearing only a wingsuit and negotiate the topography of a mountainous landscape speeding past at 260km per hour.

It is now known that efficient transmission of colour information is achieved by a transformation of the initial three trivariant colour mechanisms of rods and cones into one achromatic and two chromatic channels. But another processing stage has now been recognised that dynamically readjusts the eye’s trivariant responses to meet criteria of efficient colour information management and to provide us with all the necessary contextualising details as we survey the world around us. Discussion of opponent-processing is dealt with in the next article!

Caption [Humans differentiate between 200 hues in the visible spectrum]

Caption [Humans differentiate between 200 hues in the visible spectrum]

Müller cells

Müller glia, or Müller cells, are a type of retinal cell that serve as support cells for neurons, as other types of glial cells do.

An important role of Müller cells is to funnel light to the rod and cone photoreceptors from the outer surface of the retina to where the photoreceptors are located.

Other functions include maintaining the structural and functional stability of retinal cells. They regulate the extracellular environment, remove debris, provide electrical insulation of the photoreceptors and other neurons, and mechanical support for the fabric of the retina.

- All glial cells (or simply glia), are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system.

- Müller cells are the most common type of glial cell found in the retina. While their cell bodies are located in the inner nuclear layer of the retina, they span the entire retina.

Caption

Caption

Pigment epithelium

Pigment epithelium is a layer of cells at the boundary between the retina and the eyeball that nourish neurons within the retina. It is firmly attached to the underlying choroid is the connective tissue that forms the eyeball on one side but less firmly connected to retinal visual cells on the other.

Caption

Caption

Optic nerve

The optic nerve is the cable–like grouping of nerve fibres formed from the axons of ganglion cells that transmit visual information towards the lateral geniculate nucleus.

The optic nerve contains around a million fibres and transports the continuous stream of data that arrives from rods, cones and interneurons (bipolar, amacrine cells). The optic nerve is a parallel communication cable that enables every fibre to represent distinct information about the presence of light in each region of the visual field.

Caption

Caption

Optic chiasm

The optic chiasm is the part of the brain where the optic nerves partially cross. It is located at the bottom of the brain immediately below the hypothalamus.

The cross-over of optic nerve fibres at the optic chiasm allows the visual cortex to receive the same hemispheric visual field from both eyes. Superimposing and processing these monocular visual signals allows the visual cortex to generate binocular and stereoscopic vision.

So, the right visual cortex receives the temporal visual field of the left eye, and the nasal visual field of the right eye, which results in the right visual cortex producing a binocular image of the left hemispheric visual field. The net result of optic nerves crossing over at the optic chiasm is for the right cerebral hemisphere to sense and process left-hemispheric vision, and for the left cerebral hemisphere to sense and process right-hemispheric vision.

Caption [Hemispheric visual field diagram]

Caption [Hemispheric visual field diagram]

Lateral geniculate nucleus

The lateral geniculate nucleus is a relay centre on the visual pathway from the eyeball to the brain. It receives sensory input from the retina via the axons of ganglion cells.

The thalamus which houses the lateral geniculate nucleus is a small structure within the brain, located just above the brain stem between the cerebral cortex and the midbrain with extensive nerve connections to both.

The lateral geniculate nucleus is the central connection for the optic nerve to the occipital lobe of the brain, particularly the primary visual cortex.

Both the left and right hemispheres of the brain have a lateral geniculate nucleus.

There are three major cell types in the lateral geniculate nucleus which connect to three distinct types of ganglion cells:

- P ganglion cells send axons to the parvocellular layer of the lateral geniculate nucleus.

- M ganglion cells send axons to the magnocellular layer.

- K ganglion cells send axons to a koniocellular layer.

The lateral geniculate nucleus specialises in calculations based on the information it receives from both the eyes and from the brain. Calculations include resolving temporal and spatial correlations between different inputs. This means that things can be organised in terms of the sequence of events over time and the spatial relationship of things within the overall field of view.

Some of the correlations deal with signals received from one eye but not the other. Some deal with the left and right semi-fields of view captured by both eyes. As a result, they help to produce a three-dimensional representation of the field of view of an observer.

- The outputs of the lateral geniculate nucleus serve several functions. Some are directed towards the eyes, others are directed towards the brain.

- A signal is provided to control the vergence of the two eyes so they converge at the principal plane of interest in object-space at any particular moment.

- Computations within the lateral geniculate nucleus determine the position of every major element in object-space relative to the observer. The motion of the eyes enables a larger stereoscopic mapping of the visual field to be achieved.

- A tag is provided for each major element in the central field of view of object-space. The accumulated tags are attached to the features in the merged visual fields and are forwarded to the primary visual cortex.

- Another tag is provided for each major element in the visual field describing the velocity of the major elements based on changes in position over time. The velocity tags (particularly those associated with the peripheral field of view) are also used to determine the direction the organism is moving relative to object-space.

Caption

Caption

Optic radiation

The optic radiations are tracts formed from the axons of neurons located in the lateral geniculate nucleus and lead to areas within the primary visual cortex. There is an optic radiation on each side of the brain. They carry visual information through lower and upper divisions to their corresponding cerebral hemisphere.

Caption

Caption

Primary visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is part of the cerebral cortex and processes visual information. It is in the occipital lobe at the back of the head.

Visual information coming from the eyes goes through the lateral geniculate nucleus within the thalamus and then continues towards the point where it enters the brain. The point where the visual cortex receives sensory inputs is also the point where there is a vast expansion in the number of neurons.

Both cerebral hemispheres contain a visual cortex. The visual cortex in the left hemisphere receives signals from the right visual field, and the visual cortex in the right hemisphere receives signals from the left visual field.

Caption [Cerebral hemispheres, occipital lobes, primary visual cortex, optical radiations]

Caption [Cerebral hemispheres, occipital lobes, primary visual cortex, optical radiations]